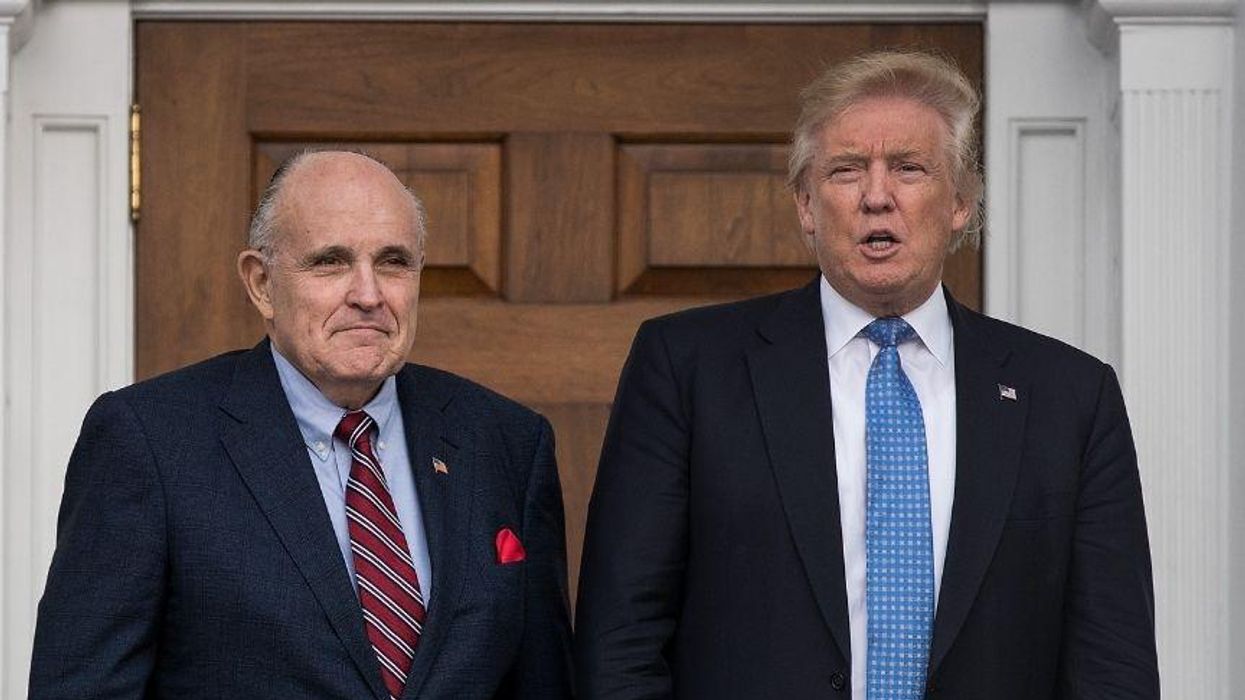

With two grand juries now looking into efforts by former President Donald Trump and his campaign to illegally influence the Georgia elections, attention has been turning to one state law in Georgia that could land both the president and his personal lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, in trouble.

Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis is reportedly looking into a provision in Georgia law that makes it a crime, punishable by at least one and up to five years in prison, for making false statements to government officials. Title 16 (Crimes and Offenses) Section 16-10-20 of the Georgia Code covers such false statements and makes it illegal to

"knowingly and willfully...make[] a false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation...in any matter within the jurisdiction of any department or agency of state government or of the government of any county, city, or other political subdivision of this state...."

This statute might be relevant to the ongoing investigations and the three cases referred to Willis's office by the Georgia Secretary of State. Two specific instances are likely top of mind for prosecutors.

First, during his phone call to Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, former President Trump made numerous false claims in order to urge Raffensperger to "find 11,780 votes" and overturn the election results. Per the Washington Post, which first broke the story, Trump walked through a laundry list of disinformation and conspiracy theories during the infamous, recorded call. These included statements that thousands of dead people had voted, that an Atlanta election worker scanned 18,000 forged ballots three times each with "100 percent" for Biden, and that thousands of voters living outside of Georgia came back just to vote against him illegally. None of these was in any way true, and all had been debunked by Georgia state election officials.

For his part, Rudy Giuliani went before Republican House members of the Georgia state legislature and claimed there was a video showing election workers taking votes out of suitcases and accused them of "passing dope, not just ballots," according to reports of the hearing. Echoing statements by former Trump campaign lawyer Sidney Powell, Giuliani claimed that the state had counted 96,000 "phantom votes" and then proceeded to parade discredited witnesses to give oxygen to the idea that voting machines were compromised. Giuliani's exposure under the "false statements" law in Georgia might have particular salience, as he was far more brazen than the ex-president in his wild assertions, and Trump has always been careful to leave a bit of plausible deniability.

The toughest part might be proving that Trump and Giuliani actually knew that their wild claims were false. After all, most of the people who subscribe to the Big Lie actually believe there was widespread election fraud and that the results are illegitimate. We are learning that this appears to include those whom the former president incited to storm the Capitol. And Trump and Giuliani have always at least made a good showing that they believe their own lies.

But the former president's legal team will have to walk an interesting tightrope in the weeks ahead. To defend against the defamation actions brought by Dominion Voting Systems and Smartmatic, they may choose to hide behind the First Amendment and claim that they had a right to assert even the wildest of claims, even ones which no reasonable person would accept as fact, just as Sidney Powell's lawyers have recently argued. This would seem to cut against the notion that the defendants believed the conspiracies they were promoting were in fact true.

All of this shows that our legal system isn't set up very well to punish people who recklessly spread misinformation, even to government officials. If the standard here were set higher to include a reckless disregard for the truth—what comprises "actual malice" in the eyes of the Supreme Court—then the case would be stronger, but it might then arguably run into First Amendment issues.

Where do you draw the line between asserting something as important as possible election fraud and reckless dissemination of false conspiracies? It always falls back to what the truth really is, and what reasonable people would know it to be.

As things stand, in order not to undercut the Big Lie, the defendants likely will assert that the statements were in fact true and they are standing by their claims, which means that even after the facts are proven to be false, they can still claim they did not "knowingly and willfully" make untrue claims to any government officials.

But there are still two problems with this defense.

First is the chance, however small, that there is a smoking gun, in the form of testimony or a written or recorded communication, revealing the team knew that the lies and conspiracies they were promoting were false but did it anyway.

Prosecutors understand that they will have to get at least one member of the team to cooperate in order to produce such testimony or such evidence, so they will begin to lean on them to see if there are weaknesses. Both Powell and erstwhile "kraken" lawyer Lin Wood are estranged from the former president and his team and in many ways were left out in the cold, so there may be opportunities there.

Second, if the claims about dead or out-of-state voters and illegally stuffing ballot boxes were true ,as they state, then why didn't the Trump campaign include the wildest ones in their court filings and argue them with the same gusto that they presented before the Georgia House members?

A jury could infer from this that Giuliani knew that he was putting on false political theater with his hearings, but that he had no leg to stand on in Court with the claims, where he could be sanctioned for such a filing or argument. That could lead the jury to conclude he knew precisely what he was doing and did in fact violate the Georgia statute prohibiting false statements to government officials.

The grand juries in Georgia will begin subpoenaing documents around the alleged election interference, and we can expect they likely will result in some indictments. Under what statutes, against whom, and with what possible penalties remains to be seen.

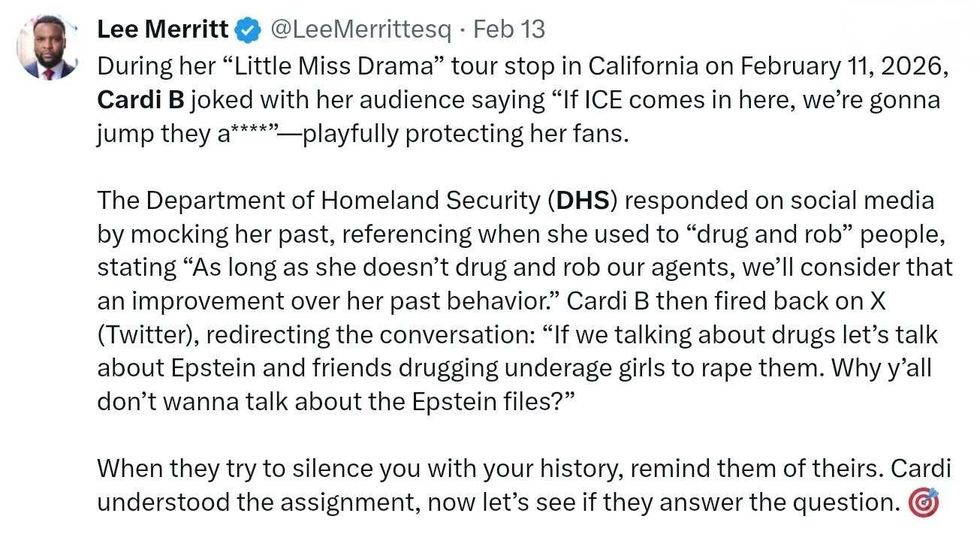

@LeeMerrittesq/X

@LeeMerrittesq/X @bob_moss/X

@bob_moss/X @jelanijones/Bluesky

@jelanijones/Bluesky @Aurkayne/X

@Aurkayne/X @sadcommunistdog; @froglok/Bluesky

@sadcommunistdog; @froglok/Bluesky