Now that Trump has been acquitted by the Senate, there's no way under the impeachment provisions of the Constitution to bar him from federal public office. That means Trump can run again in 2024.

Unless...

There is now another provision of the Constitution openly being discussed and championed, one which has not been used in over 100 years. That provision is contained within the 14th Amendment, Section 3 and states as follows:

"No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any state, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any state legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any state, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability." (Emphasis added.)

This is known as the "insurrection" exception to holding federal office. It was added after the Civil War to ensure that leaders of the Confederacy couldn't win office and sit as members of Congress after their defeat. The bar was vigorously enforced until 1872, after which an amnesty for all Confederate officers was granted.

Under Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, Congress could enact a bill naming certain officials (e.g. Trump) as having engaged in insurrection or given aid or comfort to the enemies of the United States. Just last month, such a bill was under quiet consideration by Senators Tim Kaine (D-VA) and Susan Collins (R-ME) in advance of the impeachment trial. It was dismissed as a needless distraction, but it might still gain traction now, if members of the Senate want to bar Trump from running in 2024.

With simple majority votes in the House and Senate, the bill could pass.

Some argue that this would be an illegal "bill of attainder," defined as "a legislative act which inflicts punishment without a judicial trial." But the legislative history in drafting this section undermines this, because the question of bills of attainder was debated and settled in the course of the Amendment's proposal, meaning either that this is not a criminal punishment covered by the prohibition, or it is an express exception carved later into the Constitution.

Even if Trump challenges such a bill in court, he might very well lose.

The evidence against him is staggering, and very little of the evidence deployed during the impeachment trial would be permitted in court. The rules of evidence are much stricter in a court of law, after all. Further, courts might strongly defer to Congress's factual findings in such a bill, given the language and historical purpose of the Amendment.

Others argue that should we open this possibility up, future Republican majorities would use it to bar Democrats from holding office, simply by branding them as "enemies of the United States." The counter-argument is that we have never before seen the likes of the January 6 insurrection. Extraordinary times require extraordinary measures, and therefore such a measure would be of limited precedent value.

Finally, some argue that this would comprise a second impeachment trial of Trump, and his supporters would simply cite this as another example of his continued victimization. It would be a media distraction from important goals the new administration wants to achieve.

One way around these problems is perhaps a quieter lobby, where such a bill receives the blessing of Mitch McConnell and is announced with strong bipartisan support. Given the desire of many GOP leaders like McConnell to move beyond the era of Trump, such an approach might be politically feasible.

This article was originally published on The StatusKuo Substack here and is reprinted with the author's permission.

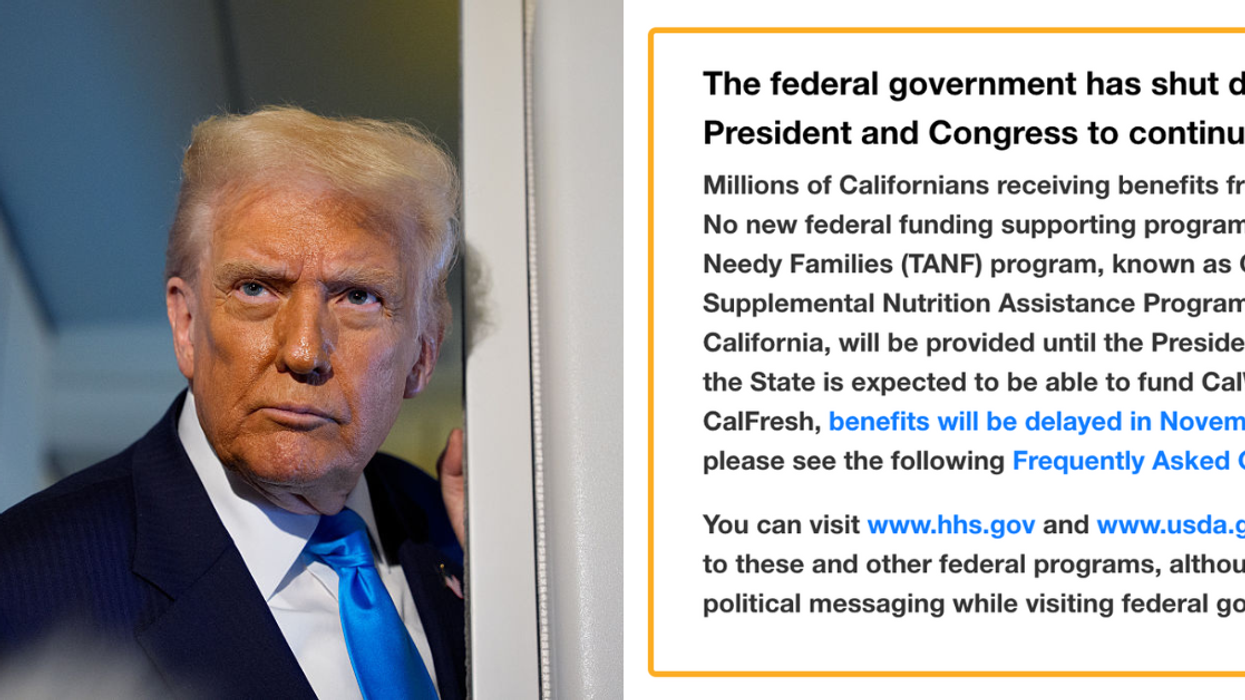

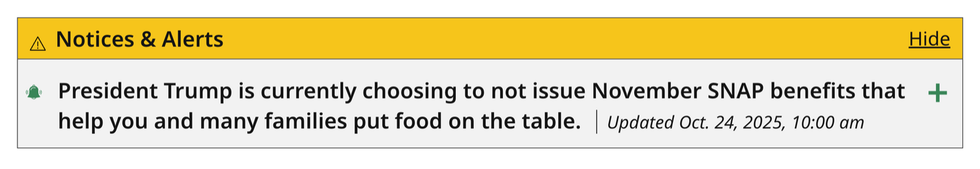

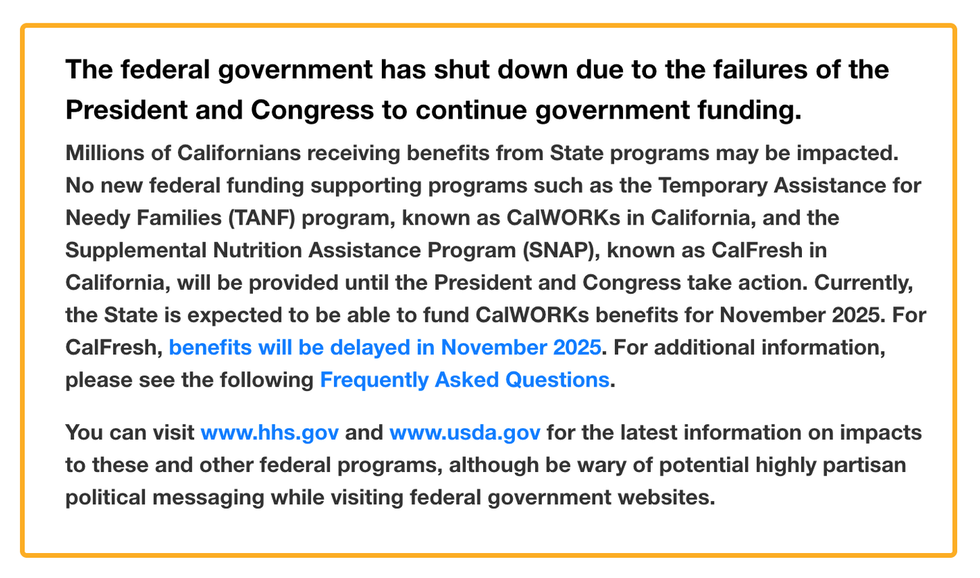

mass.gov

mass.gov cdss.ca.gov

cdss.ca.gov

Sad Break Up GIF by Ordinary Frends

Sad Break Up GIF by Ordinary Frends  so what who cares tv show GIF

so what who cares tv show GIF  Iron Man Eye Roll GIF

Iron Man Eye Roll GIF  Angry Fight GIF by Bombay Softwares

Angry Fight GIF by Bombay Softwares

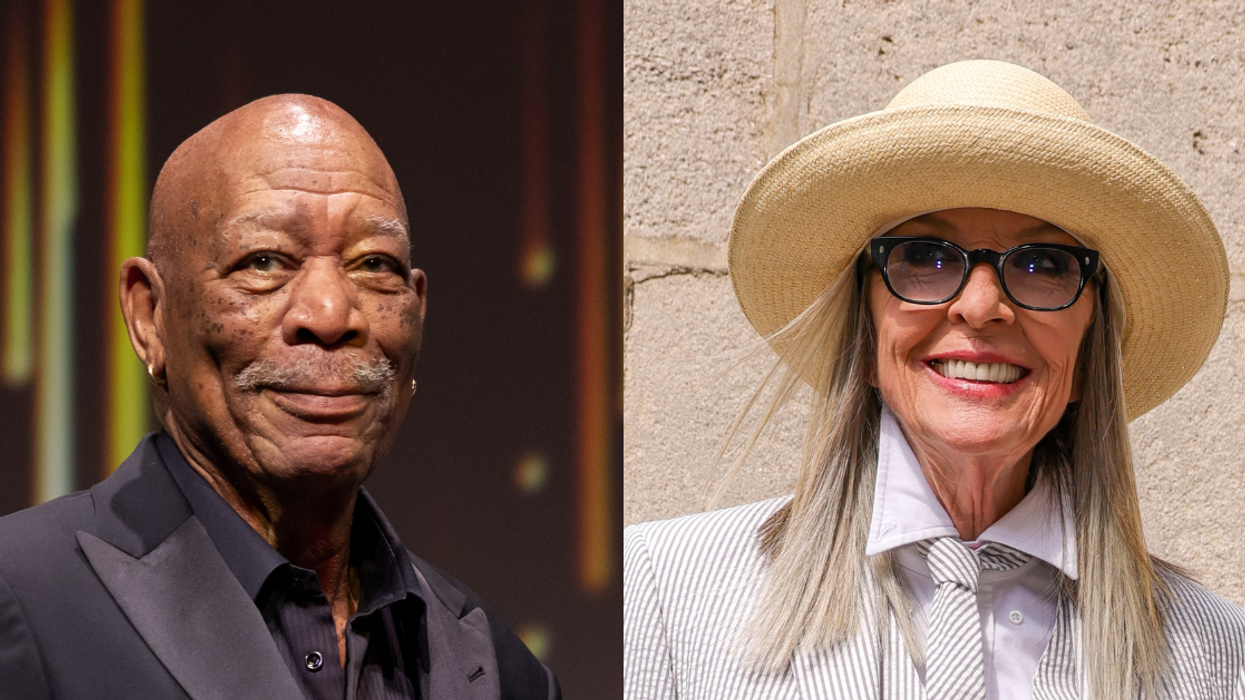

@jimmykimmellive/Instagram

@jimmykimmellive/Instagram @jimmykimmellive/Instagram

@jimmykimmellive/Instagram @jimmykimmellive/Instagram

@jimmykimmellive/Instagram @jimmykimmellive/Instagram

@jimmykimmellive/Instagram @jimmykimmellive/Instagram

@jimmykimmellive/Instagram @jimmykimmellive/Instagram

@jimmykimmellive/Instagram @jimmykimmellive/Instagram

@jimmykimmellive/Instagram @jimmykimmellive/Instagram

@jimmykimmellive/Instagram @jimmykimmellive/Instagram

@jimmykimmellive/Instagram @jimmykimmellive/Instagram

@jimmykimmellive/Instagram @jimmykimmellive/Instagram

@jimmykimmellive/Instagram @jimmykimmellive/Instagram

@jimmykimmellive/Instagram @jimmykimmellive/Instagram

@jimmykimmellive/Instagram @jimmykimmellive/Instagram

@jimmykimmellive/Instagram