Surgeons often use metal pieces such as screws and plates to hold broken bones together. Soon, there may be another, better option: ceramic implants created by 3D printers.

Many researchers have touted the medical promise of additive manufacturing, more commonly known as 3D printing. As the technology has become cheaper and more precise, the medical community has embraced it, creating things like prosthetic limbs, tissue with blood vessels, and even biosynthetic ovaries using 3D printing techniques. Now Hala Zreiqat, a professor of biomedical engineering at the University of Sydney in Australia, has shown the capacity for 3D printed implants to heal broken bones by not just holding them together, but encouraging new bone growth.

Zreiqat and her team had previously tested their hypothesis on rabbits, using the 3D printed material to heal their broken arms. In a new study that has yet to be published, they worked with large leg fractures in sheep, 25 percent of which were completely healed after three months, and 88 percent of which were healed after one year.

The material Zreiqat and her colleagues created is porous and made of a multicomponent ceramic with calcium, silicon, strontium, and zinc elements, giving it a similar composition to that of real human or animal bone.

“The bone substitute my team and I developed...mimics the way real bone withstands loads and deflects impacts; and, like real bone, contains pores that allow blood and nutrients to penetrate it,” she said.

The implant also goes a step further, by acting as a scaffold that dissolves into — and re-strengthens — existing bone.

“The fact that our material actually kick-starts bone regeneration makes it far superior to other available materials,” Zreiqat said.

In the sheep study, which is a precursor to studying the implant in humans, the sheep reportedly were able to walk immediately after surgery, and most were fully healed after a year. They also did not appear to suffer any major side effects, which is a promising sign since implants can sometimes be rejected by the patient’s body. That took some testing, according to the researchers, who said they had to adjust the different elements of the ceramic “bone” several times over the course of a year.

“They got their old bones back,” Zreiqat said.

This news comes just a few months after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a 3D printed cervical device for use in the human spine. Rather than ceramic, these devices are made of metal, but they similarly mimic the characteristics of real bone, with a spongy center and hard exterior. And just like in the sheep’s fractured legs, these metal scaffolding implants encourage tissue to grow through them and heal the surrounding bone.

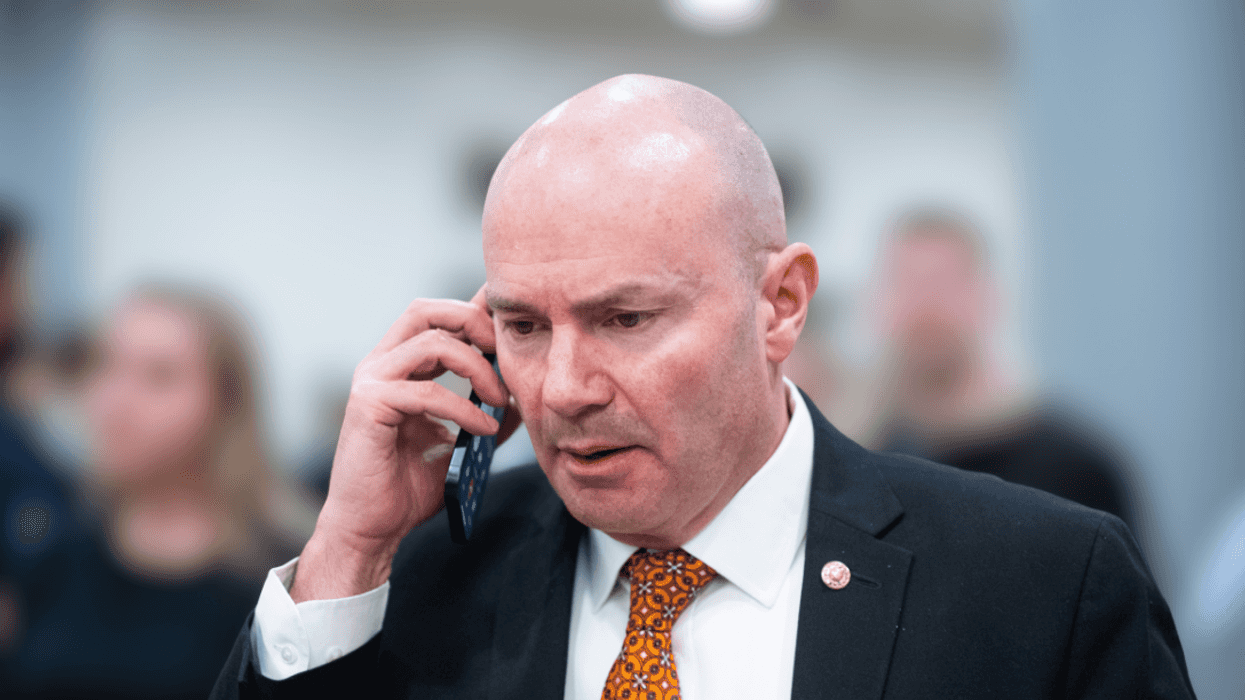

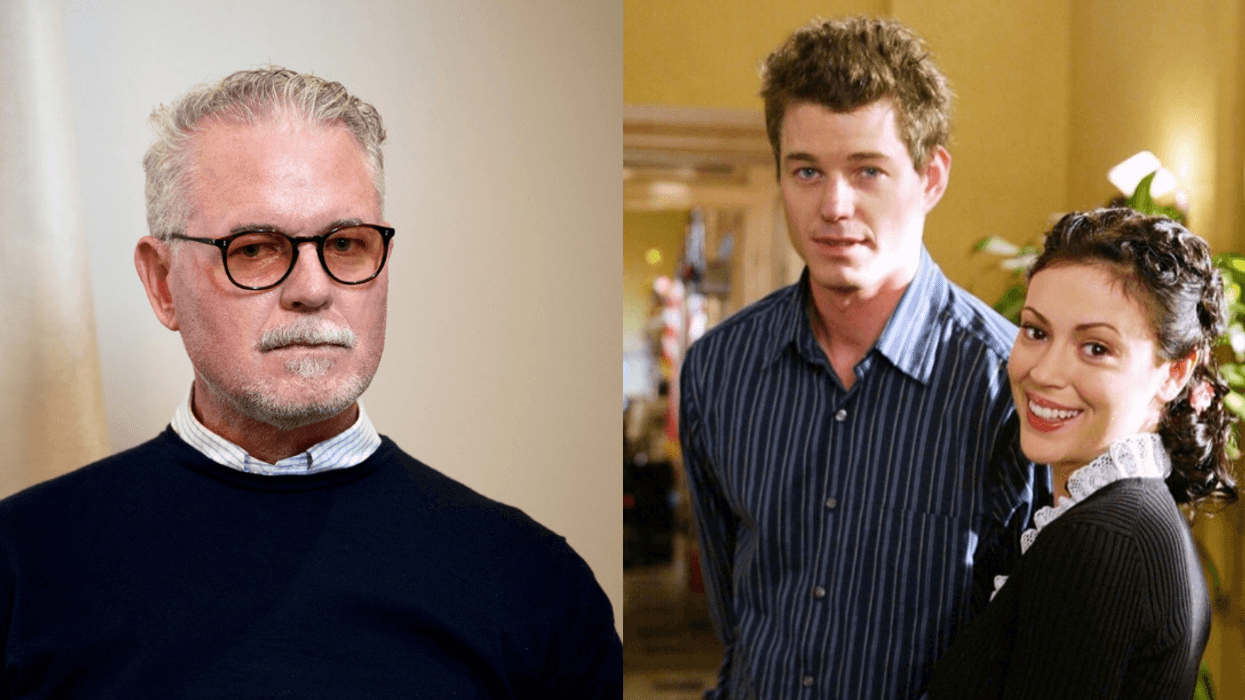

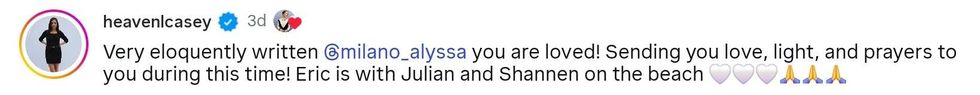

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

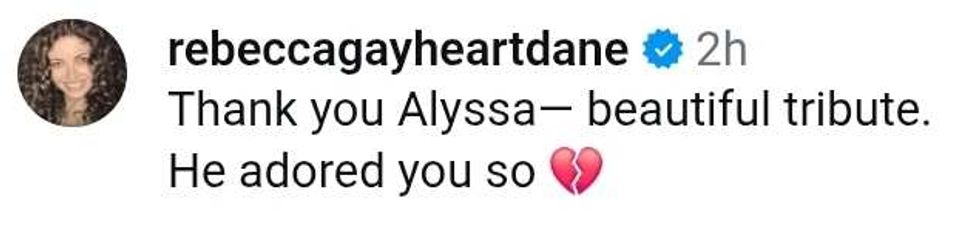

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @rebeccagayheartdame/Instagram

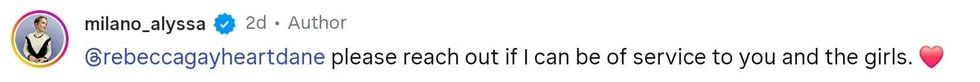

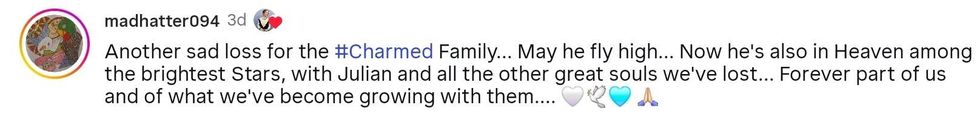

reply to @rebeccagayheartdame/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

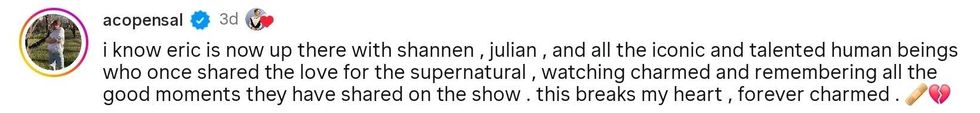

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

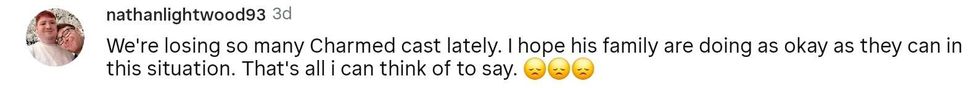

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

reply to @milano_alyssa/Instagram

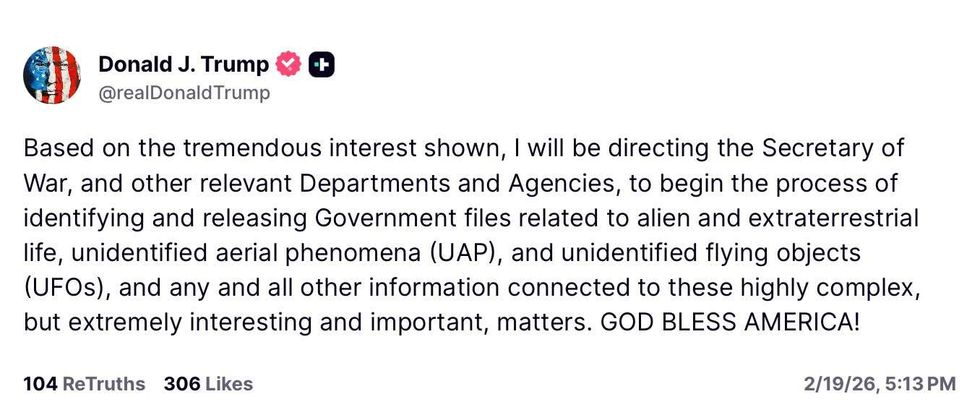

@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social

@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social

@gutterutterart/Instagram

@gutterutterart/Instagram @gutterutterart/Instagram

@gutterutterart/Instagram @gutterutterart/Instagram

@gutterutterart/Instagram @gutterutterart/Instagram

@gutterutterart/Instagram @gutterutterart/Instagram

@gutterutterart/Instagram @gutterutterart/Instagram

@gutterutterart/Instagram @gutterutterart/Instagram

@gutterutterart/Instagram @gutterutterart/Instagram

@gutterutterart/Instagram @gutterutterart/Instagram

@gutterutterart/Instagram @gutterutterart/Instagram

@gutterutterart/Instagram @gutterutterart/Instagram

@gutterutterart/Instagram