Conservative news reports in the aftermath of last month's mass shooting at a high school in Parkland, Florida, searched for an adequate scapegoat to blame for the deaths of 17 people.

They found one––in the form of the School Discipline Guidance Package to Enhance School Climate and Improve School Discipline Policies/Practices, an Obama-era guidance document which sought to curb the suspensions and expulsions of minority students and effectively discouraged schools from reporting misbehaving students to law enforcement.

One of the more prominent critics of the Obama-era guidance is Paul Sperry, a conservative political commentator and former Hoover Institution media fellow, who. as recently as the beginning of this month, wrote in an article for Real Clear Investigations that:

Despite committing a string of arrestable offenses on campus before the Florida school shooting, Nikolas Cruz was able to escape the attention of law enforcement, pass a background check and purchase the weapon he used to slaughter three staff members and 14 fellow students because of Obama administration efforts to make school discipline more lenient.

This wasn't the first time Sperry criticized the guidance, however. He waxes indignant in a more widely circulated piece for The New York Post dated December 23, 2017:

Since President Barack Obama pressured educators to adopt a new code of conduct making it harder to suspend or expel students of color, even kids who punch out their teacher aren’t automatically kicked out of school anymore.

Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL), who has faced boundless criticism over not just his response to the Parkland shooting––which many survivors and their families regard as hollow––but for his record of accepting contributions from the NRA, then wrote a letter addressed to Attorney General Jeff Sessions and Education Secretary Betsy DeVos questioning whether the guidance allowed Nikolas Cruz, the gunman, to evade law enforcement and carry out the shooting:

A January 2014 directive, “Dear Colleague Letter on the Nondiscriminatory Administration of School Discipline,” and subsequent guidance developed by the Department of Education, in collaboration with the Department of Justice, discouraged schools from referring students to local law enforcement. The 2014 guidance encouraged schools to emphasize “constructive interventions” over certain disciplinary actions. This guidance also states that school policies should “[e]nsure that school personnel understand that they, rather than school resource officers and other security or law enforcement personnel, are responsible for administering routine student discipline.” This policy allowed the Departments to initiate an investigation into schools and, if found to be noncompliant, could be at risk of losing federal funding. Further, the 2014 directive and subsequent guidance included onerous requirements and harsh penalties that arguably made it easier for schools to not report students to law enforcement than deal with the potential consequences.

Rubio goes on to express his belief that the "overarching goals of the 2014 directive to mitigate the school-to-prison pipeline, reduce suspensions and expulsions, and to prevent racially biased discipline are laudable and should be explored," but notes that "any policy seeking to achieve these goals requires basic common sense and an understanding that failure to report troubled students, like Cruz, to law enforcement can have dangerous repercussions."

He closes with a call for Sessions and DeVos to "immediately revise" the directive:

To that end, I strongly urge you to immediately revise the 2014 directive and associated guidance to ensure that schools appropriately report violence and dangerous actions to local law enforcement. These revisions must take into account input from state and local education agencies, law enforcement, and behavioral health specialists. Additionally, states should not fear harsh, financial repercussions for reporting a student to law enforcement, if that student is reasonably believed to be a threat to themselves or others. As you begin this process, I respectfully request to receive updates on the revisions as necessary.

According to The New York Times, Broward County Educators and advocates "saw Mr. Rubio's letter as an indictment of a program called Promise, which the county instituted in 2013 — one year before the Obama guidance was issued — and has guided its discipline reforms to reduce student-based arrests in Broward County, where Stoneman Douglas is located."

Rubio released a proposal that he claims would apply the necessary fixes to both Promise and the Obama directive in the days before he submitted his letter to Sessions and DeVos. In tweets earlier today, he acknowledges that Cruz was not in the Promise program, but that he did display violent behavior.

There are three significant problems with these criticisms of the Obama directive:

- The first: Minority students have historically and empirically not been the perpetrators of the mass shootings which appear to have proliferated the media and public discourse, nor have minority schools been the targets of these shootings.

- The second: Nikolas Cruz is, in fact, white, was adopted by a Hispanic couple shortly after his birth, and trained at a“white separatist paramilitary proto-fascist organization” in Tallahassee, per a statement from Jordan Jereb, a captain of the Republic of Florida, and a report by the Anti-Defamation League.

- The third: Cruz did not evade school disciplinary procedures. Administrators expelled him from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School before the shooting and police had been called to the residence where he lived with his mother, Lynda, who died in November, more than once to deal with behavioral problems and other familial disputes.

Nevertheless, President Donald Trump appears to have taken cues from Rubio and his conservative base, and has announced that Secretary DeVos will chair a school safety commission which will weigh in on policy changes, including examining the “repeal of the Obama administration’s ‘Rethink School Discipline’ policies.”

Teachers' advocates voiced their disapproval. Among them: Catherine Lhamon, the former Education Department assistant secretary for civil rights under Barack Obama. She says that protecting schools from mass shootings is an entirely different job to managing school discipline so it doesn't discriminate against minority and disabled students.

“It is completely divorced and should be completely divorced from how to address external shooters,” she tells USA Today.

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, adds that the president's proposal to arm educators won't make students feel any safer.

“You need to spend one nanosecond in schools to know that making schools like penitentiaries will not help children thrive,” she said. She noted that schools should be "more welcoming and safe environments” so students like Cruz can receive the help they need.

“The state never did what it needed to do to get the kid services outside of the school system,” she said, referring to other agencies which had failed to help Cruz even before his behavior at Stoneman Douglas became intolerable.

At the time the Obama-era guidance was issued, federal data found that African-American students without disabilities were more than three times as likely as their white peers without disabilities to be expelled or suspended. The data also revealed that more than 50 percent of students who were involved in school-related arrests or who were referred to law enforcement were Hispanic or African-American.

“Children’s safety also includes protection from oppression and bigotry and injustice,” wrote Daniel J. Losen, the director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the University of California at Los Angeles’s Civil Rights Project, in testimony to the Civil Rights Commission. He adds: “Fear-mongering and rhetoric that criminalizes youth of color, children from poor families and children with disabilities should not be tolerated.”

Secretary DeVos has come under fire for her decision to rescind numerous regulations that outline the rights of students with disabilities, including one that protects against racial disparities in special education placements. She has said the Department of Education wants to be “sensitive to all of the parties involved.”

In an interview with 60 Minutes over the weekend, DeVos claimed that disproportionate disciplinary actions “comes down to individual kids," and declined to answer when asked if she believed that black students who face harsher disciplinary measures are the victims of institutional racism.

“We’re studying it carefully and are committed to making sure students have opportunity to learn in safe and nurturing environments,” she said.

In July 2017, the Department of Education announced it would scale back investigations into civil rights violations at public schools and universities, in a rebuke of mandates imposed by the Obama administration. The current administration has deemed the mandates, like many of the regulations it has stripped, as superfluous.

@WhiteHouse/X

@WhiteHouse/X

@william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok

@carol_haynes_/Instagram

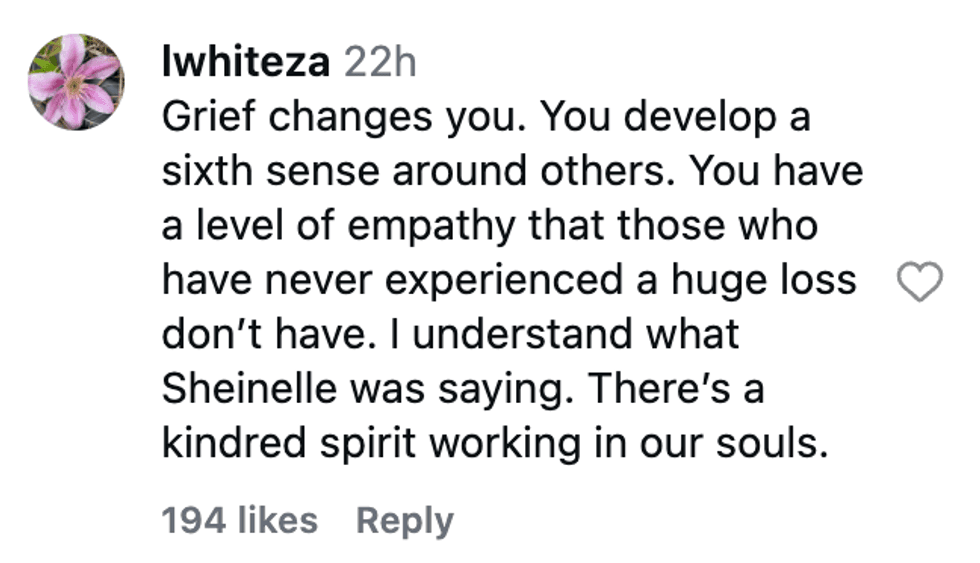

@carol_haynes_/Instagram @lwhiteza/Instagram

@lwhiteza/Instagram @iamdrkandace/Instagram

@iamdrkandace/Instagram @solveigerway/Instagram

@solveigerway/Instagram @sziulkow/Instagram

@sziulkow/Instagram @claudiatorres2019/Instagram

@claudiatorres2019/Instagram @carolken/Instagram

@carolken/Instagram @karenpayton34/Instagram

@karenpayton34/Instagram @mamaburnside/Instagram

@mamaburnside/Instagram @alr_thrives/Instagram

@alr_thrives/Instagram @dr.rxq/Instagram

@dr.rxq/Instagram @bogie1954/Instagram

@bogie1954/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram