Two previously unseen pages of Anne Frank’s diary were recently uncovered after researchers in Amsterdam were able to access the pages using digital image-processing technology. The long-standing concern was that separation of the pages might damage the integrity of the famous white-and-red plaid notebook.

The pages, which were covered by brown paper, were presented at a news conference in May.

The story goes as follows: Anne Frank tried to cover up the two pages of writing in her diary, which contained dirty jokes and, what she called, “sexual matters.” She glued or pasted brown paper over the pages to conceal them from a potential reader’s eye. At the time, she likely never believed such readers would be researchers and students of her work, but rather, her father or any of the others cramped in the hidden attic annex during World War II. Researchers at the Anne Frank House found the two obscured pages in the original version of the diary while they were monitoring its condition and photographing the pages in 2016.

The notebooks are examined once every 10 years and otherwise stored away for preservation.

“When you touch the pages they can be damaged, so we don’t touch them,” said Teresien da Silva, head of collections at the Anne Frank House.

New digital image-processing technology that only recently became available has now revealed the once-hidden text of pages 78 and 79, according to the Anne Frank House and two Dutch cultural institutions. A news conference at the Anne Frank Foundation’s office displayed a video of the text underneath the two taped pages, which were viewed without any contact with the physical pages.

“I sometimes imagine that someone might come to me and ask me to inform him about sexual matters,” Frank penned in Dutch. “How would I go about it?” Addressing an imaginary listener using an elevated voice, she attempts to answer her rhetorical questions, using phrases such as “rhythmical movements,” to describe sex, and “internal medicament,” to reference contraception.

In the pages, menstruation is another topic of discussion. She calls it “a sign that she is ripe.” On prostitution: “In Paris they have big houses for that.”

Perhaps even more fascinating than her young words on sexual subject matter is the discovery of Frank’s first real attempt at literary writing.

Senior researcher Peter de Bruijn, of the Huygens Institute for the History of the Netherlands, a partner organization in the research, explained that the pages are not significant for their content — into which she similarly delves in other parts of the diary, often even more explicitly — but rather, for their style.

“She starts with an imaginary person whom she is telling about sex, so she creates a kind of literary environment to write about a subject she’s maybe not comfortable with,” he explained.

Ronald Leopold, executive director of the Anne Frank House, said the discovery “adds meaning to our understanding of the diary,” calling it “a very cautious start to her becoming a writer” and in “very early stages.” At the time of writing, Frank was only 13 years old. The pages were written in her first of two versions of the diary, on September 28, 1942.

The first was written in a series of small notebooks, dating from her 13th birthday on June 12, 1942, to August 1, 1944, and was meant solely for her own viewing. When she learned from the radio that the Dutch government in exile was planning to publish personal accounts of people’s experiences under the German occupation, Frank decided to make her diary into a book she called “The Secret Annex.” She aspired to submit the pages for publication following the war.

She finished 215 pages in a couple of months. In August 1944, she and her family were discovered, arrested and deported to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where she died three months before her 16th birthday, in 1945.

Frank could have pasted over the hidden pages as a method of editing, according to de Bruijn, as she prepared her diary for the second version and potential publication.

Though some may consider this intentional reveal an invasion of Frank’s privacy, da Silva explained that such a discovery can teach the world much about how an artist or other great mind worked.

For example, Franz Kafka wished to destroy many of his own literary works, and yet, researchers still work to save them. Likewise, in Frank’s case, da Silva argued, “It’s not always good to follow the wish of an author. It’s important sometimes for scientific research and also good to know for the public what she didn’t want to publish.”

The Anne Frank House plans to publish the newly-discovered text on its website in Dutch for now. It is unknown when the text will become available in English.

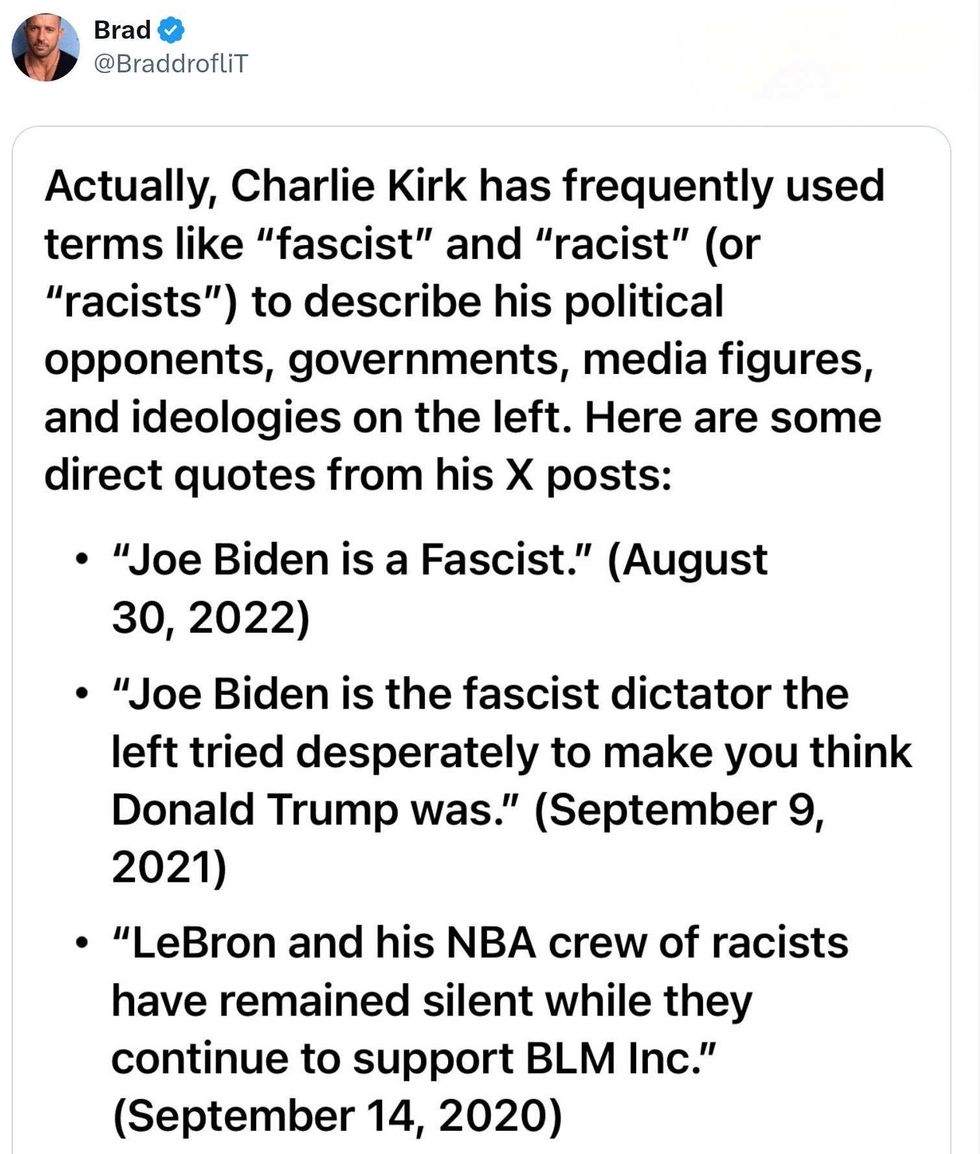

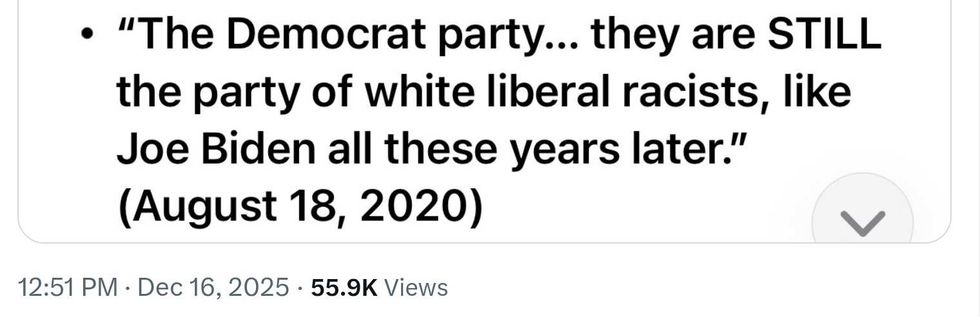

Replying to @StefanMolyneux/X

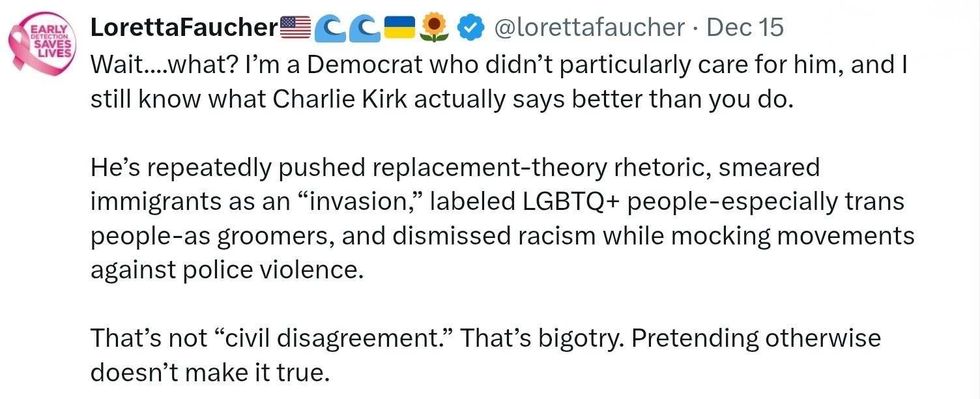

Replying to @StefanMolyneux/X Replying to @StefanMolyneux/X

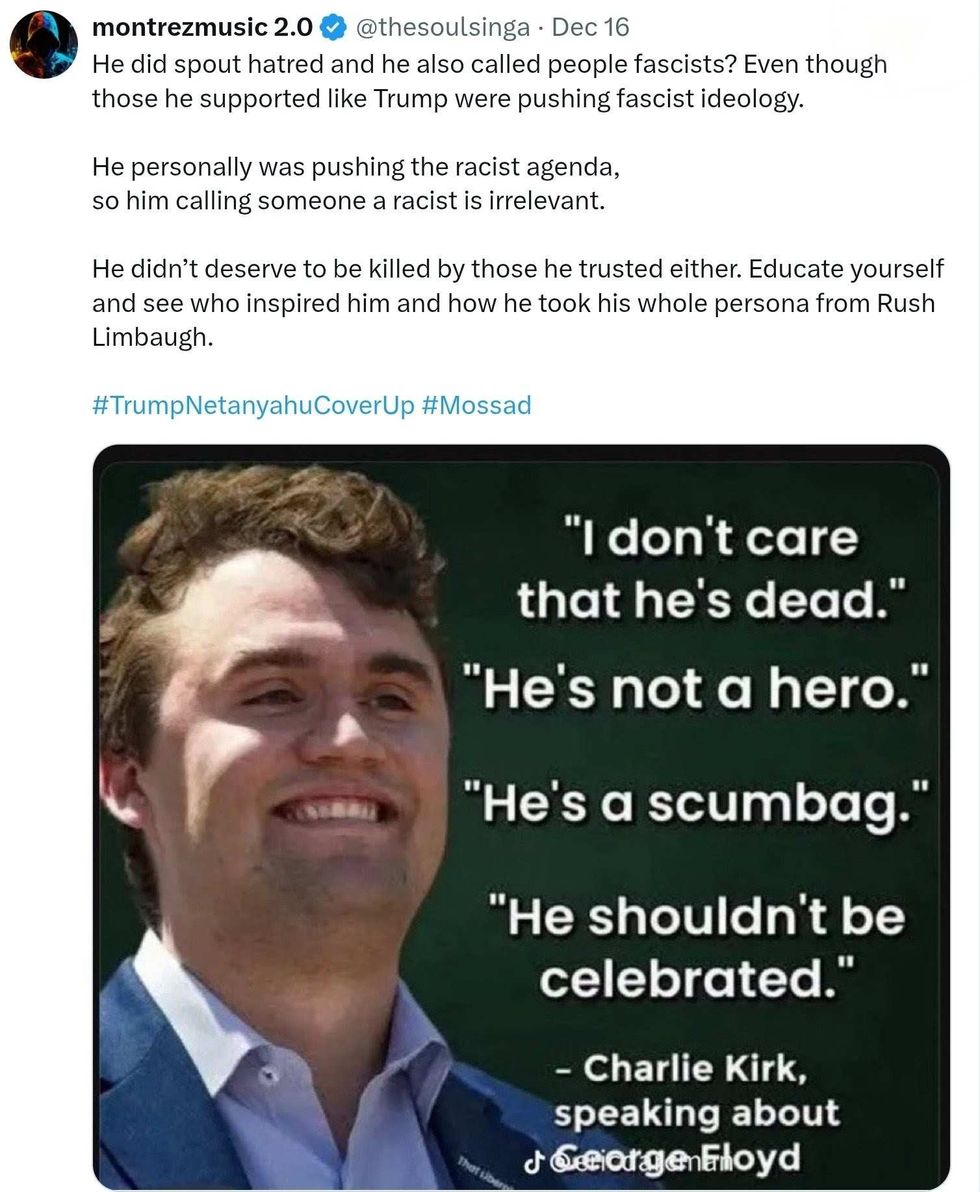

Replying to @StefanMolyneux/X Replying to @StefanMolyneux/X

Replying to @StefanMolyneux/X Replying to @StefanMolyneux/X

Replying to @StefanMolyneux/X

Playing Happy Children GIF by MOODMAN

Playing Happy Children GIF by MOODMAN  May The Fourth Be With You

May The Fourth Be With You

Nhh GIF by New Harmony High School

Nhh GIF by New Harmony High School