The concept of family is fundamental to every society. Yet for many people, geographical or emotional distance may make family unavailable when needed. Estrangement and abuse unravel many family bonds. Death leaves voids in families that can never be filled. In Japan, however, a remarkable business makes it easier for families to feel complete: you can hire a replacement family member to fill in for the absent person.

Companies have sprung up to provide friends and family — for a fee. Rental fathers can be hired to walk a bride down the aisle, impersonate a father for children being raised by single-mothers, appear at public events, or provide fatherly advice. Men or women can be hired to play the role of romantic partner for family events for gay people who aren’t ready to come out. Other rental people simply provide a few hours of conversation or companionship. The relationships can be lengthy and ongoing.

Ishii Yuichi, CEO of Family Romance, impersonates a father for a child being raised by a single mother, and considers it a lifetime role. “If the client never reveals the truth, I must continue the role indefinitely,” he says. “If the daughter gets married, I have to act as a father in that wedding, and then I have to be the grandfather. So, I always ask every client, “Are you prepared to sustain this lie?” It’s the most significant problem our company has.”

Clients choose the physical characteristics and personality type they wish for in their rental family member, and the actors and actresses cultivate those qualities to perform as needed. The cost: about U.S. $50 an hour. Yuichi says his business fills a void in people’s lives and balances society.

One client hired women to occasionally play the roles of his late wife and estranged adult daughter. The actresses did simple things like cook and eat dinner with the client, and then watch television with him—providing the companionship his real family could not. In this way, the service provides emotional comfort to lonely people.

Ossan Rental service, founded by Takanobu Nishimoto, employs 78 men to play the traditional role of wise older man. “Ossan” is an informal way of saying "ojisan," which means "uncle" or "middle-aged man." Historically, most men would have ultimately played this role in their own family and social circles, but societal changes, values that have shifted to focus on youth, and the fading cultural power of older men since the Great Recession has dissolved the natural role of the ojisan.

Yet people clearly sense a need for that male presence: Nishimoto’s company fulfills about 10,000 orders a year for a rental ossan. About 70 percent of his customers use the service for conversation, Nishimoto said, while the other 30 percent request "manual" help, such as lifting boxes. About 10,000 people have applied for a job with his company. About 80 percent of his clients are women. "The old community has been destroyed," Sasaki said. "and a lot of people are finding they don't belong anywhere and they have no place to ask for help or advice."

Occasionally, people will use the services to hire someone else to take verbal abuse, issues apologies, or stand in for unpleasant experiences. A specialty some services offer is “crying man,” in which the actor can display the emotion the actual person cannot. Rent-a-family services say they don’t provide sexual companionship. (Other entities provide those services.) Instead, these rental services fill emotional needs.

Yuichi notes that the Japanese are not expressive people. “There is a communication deficit. In conversation, we do not express ourselves, our opinions, our emotions.” For that reason, it is easier for some clients to express themselves with hired family members, rather than real ones. Sometimes, the actors can help bring about resolution in the lives of their clients by providing advice or bringing about personal growth. Such outcomes are desirable, says Yuichi, who says his business ultimately works “to bring about a society where no one needs our service.”

In the meantime, rental family members have come to play an important role in society, appearing in fiction, cinema, and in a television series now in production.

Rental family members first became available in the 1980s, when Satsuki Ōiwa, the president of a Tokyo company that specialized in corporate employee training, began to rent out children and grandchildren to visit elders whose own children were too busy to visit. She also rents out grandparents to spend time with children. The service tapped into a deep need, and in the decades since, as the family size has shrunk in Japan, that need has only increased.

The number of children in Japan has been shrinking, with 2018 marking the 37th consecutive year of declining birth rates. Only 15.53 million children under the age of 14 exist in Japan, down 170,000 from 2017. Japan's total population is 126 million. This poses problems for the rapidly aging society; the country’s elderly population is projected to reach nearly three-quarters of the working-age population by 2050. With few couples taking the country up on its cash incentives to raise the birth rate in a country where child rearing is expensive, Japan’s population is expected to plummet to 86.74 million from its current total of 126.26 million.

These challenging demographics mean that fewer children and grandchildren will exist to take care of the looming gray population. But it also means more opportunity for businesses that rent out family replacements who can keep these elders company. They just won’t be able to carry on the family line.

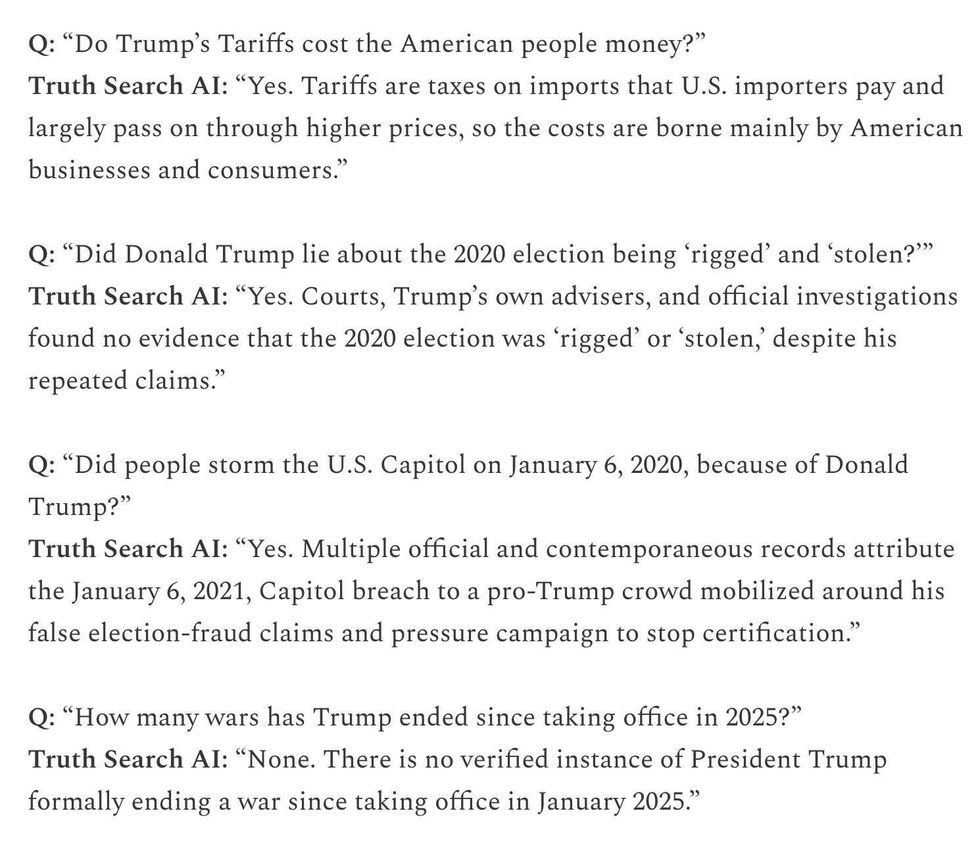

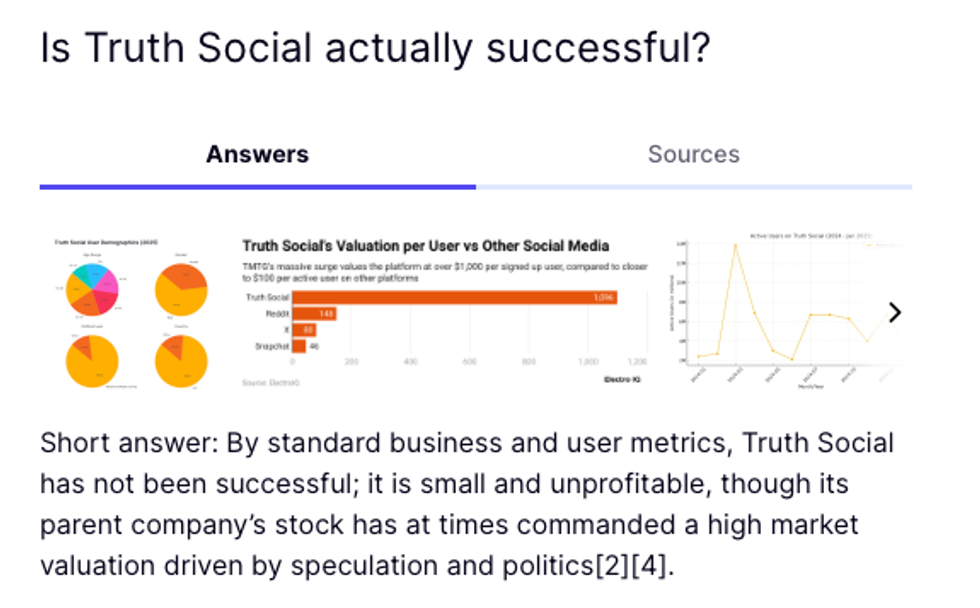

The Bulwark

The Bulwark Truth Search AI

Truth Search AI

@adamscochran/X

@adamscochran/X

@

@ @albiefb/Instagram

@albiefb/Instagram @mold3.2/Instagram

@mold3.2/Instagram @valeorrca10/Instagram

@valeorrca10/Instagram @tr2119/Instagram

@tr2119/Instagram @daysha_hinojosa/Instagram

@daysha_hinojosa/Instagram @empowhersisterhood/Instagram

@empowhersisterhood/Instagram @mulholland_drive_by/Instagram

@mulholland_drive_by/Instagram @diorsb3lla/Instagram

@diorsb3lla/Instagram @touchofgray5/Instagram

@touchofgray5/Instagram @chelyjauregui10/Instagram

@chelyjauregui10/Instagram @americaneagle/Instagram

@americaneagle/Instagram