Despite being a time when sexism should have been long-since stamped out, it’s still not unusual for women to struggle in a male-centric environment. So imagine what a woman in the field of chemistry must have gone through during the 1960s when even women’s suffrage in the United States was still relatively new, and equal rights were an even newer concept in other parts of the world.

Often relegated to administrative positions or as housewives, women weren’t known for having the opportunities to make great strides in any field. In fact, it wasn’t until after the Allied occupation of Japan that women saw equal opportunities in education in the proud empire. Yet in 1943, as World War II still raged on, Katsuko Saruhashi, the subject of today’s Google Doodle, graduated from the Imperial Women’s College of Science (now the University of Tokyo). It was a groundbreaking achievement that launched a life of successes and became a milestone for women in science.

Katsuko passed away on Sept. 29, 2007, and on her 98th birthday, Google opted to bring to light her many contributions to geochemistry. After graduating from the Imperial Women’s College of Science, Saruhashi went on to join the Meteorological Research Institute under the Central Meteorological Observatory. It was here that she got her first taste of working in a geochemical laboratory.

Within seven years of her graduation, Saruhashi became a pioneer in the study of carbon dioxide. The odorless gas was discovered in the 1750s by Scottish chemist Joseph Black, but it was Katsuko that determined the importance of CO2 and came up with a method to measure levels found in seawater. Dubbed “Saruhashi’s Table,” oceanographers have utilized the geochemist’s methodology to use pH levels, chlorinity, and temperature to measure the concentration of carbonic acid in water.

After the Bikini Atoll nuclear tests of 1954, Saruhashi became part of a team from the Geochemical Laboratory sent to monitor and analyze radioactivity in both the rain and seawater. Through her research, Saruhashi was able to measure that the fallout from the nuclear tests traveled over a year and a half before reaching Japan’s coast. Over the course of the 1970s and 1980s, she returned to studying radioactivity in water, this time looking specifically at acid rain and its lasting effects on the environment.

Over the course of her life, Saruhashi accomplished many “firsts” for women, including becoming the first to earn a doctorate in chemistry (1957), to be elected to the Science Council of Japan (1980), and to be honored with the Miyake Prize for geochemistry (1985). She also won the Avon Special Prize for Women for her research into peaceful uses of nuclear power (1981), won the Tanaka Prize from the Society of Sea Water Sciences (1993), and was named executive director of the Geochemical Laboratory (1979).

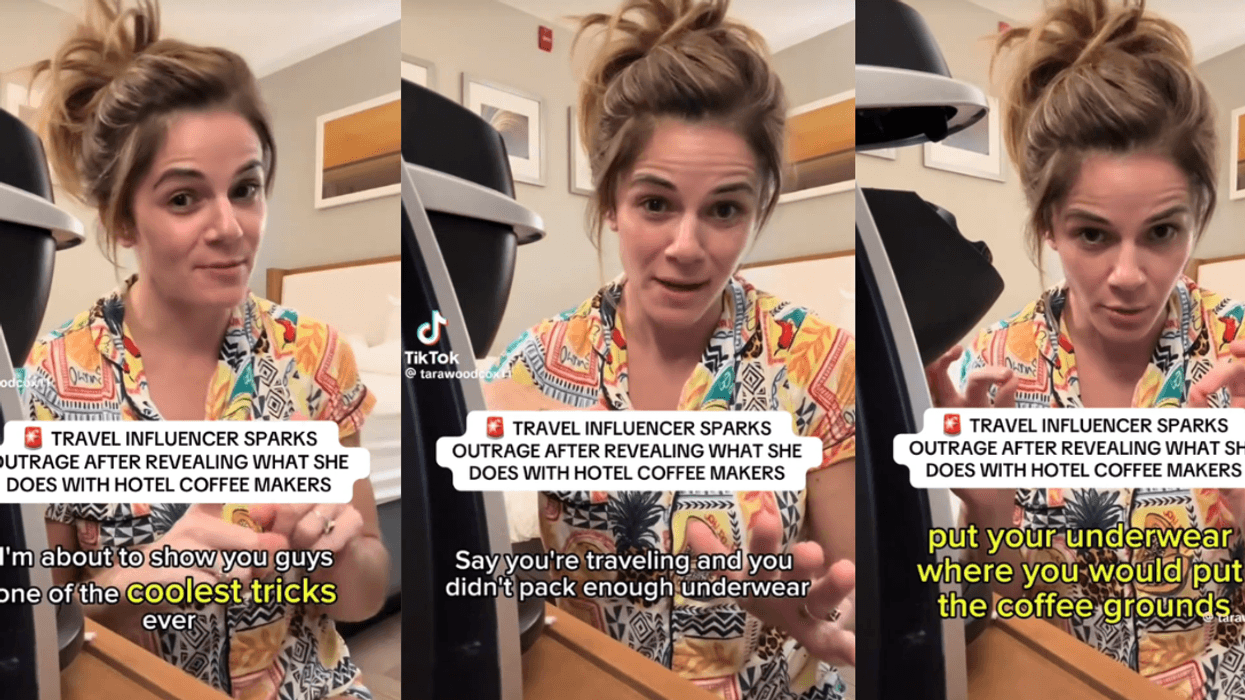

@madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok

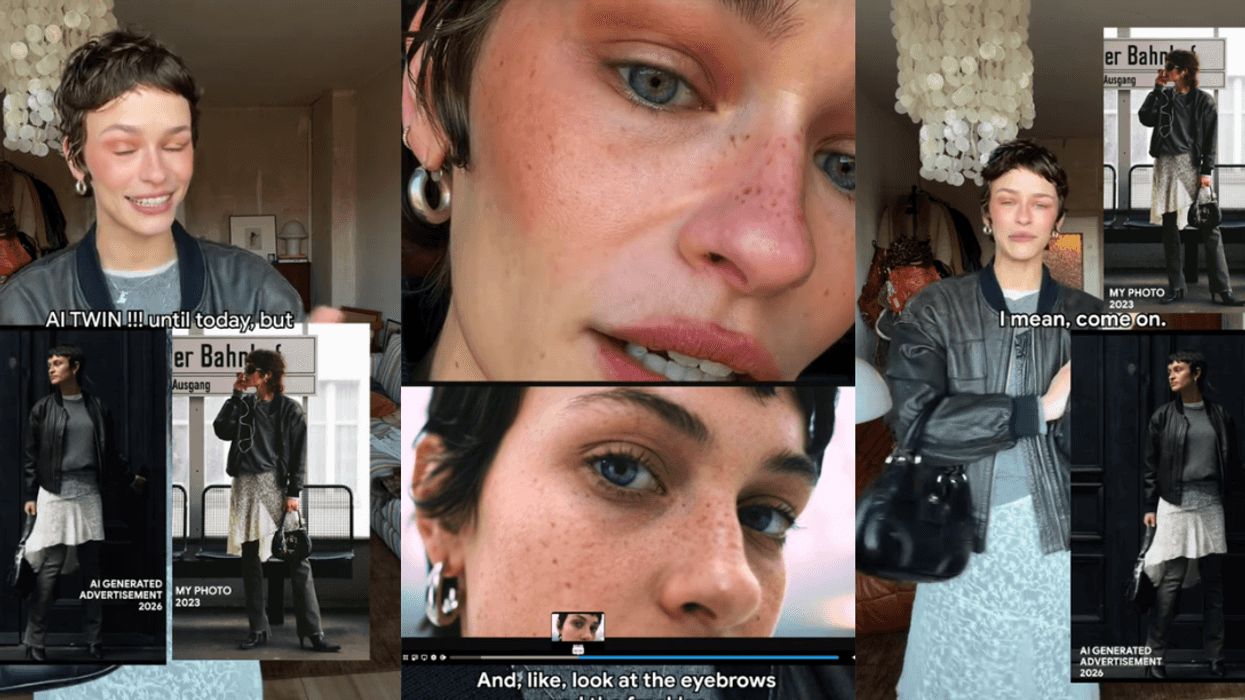

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok