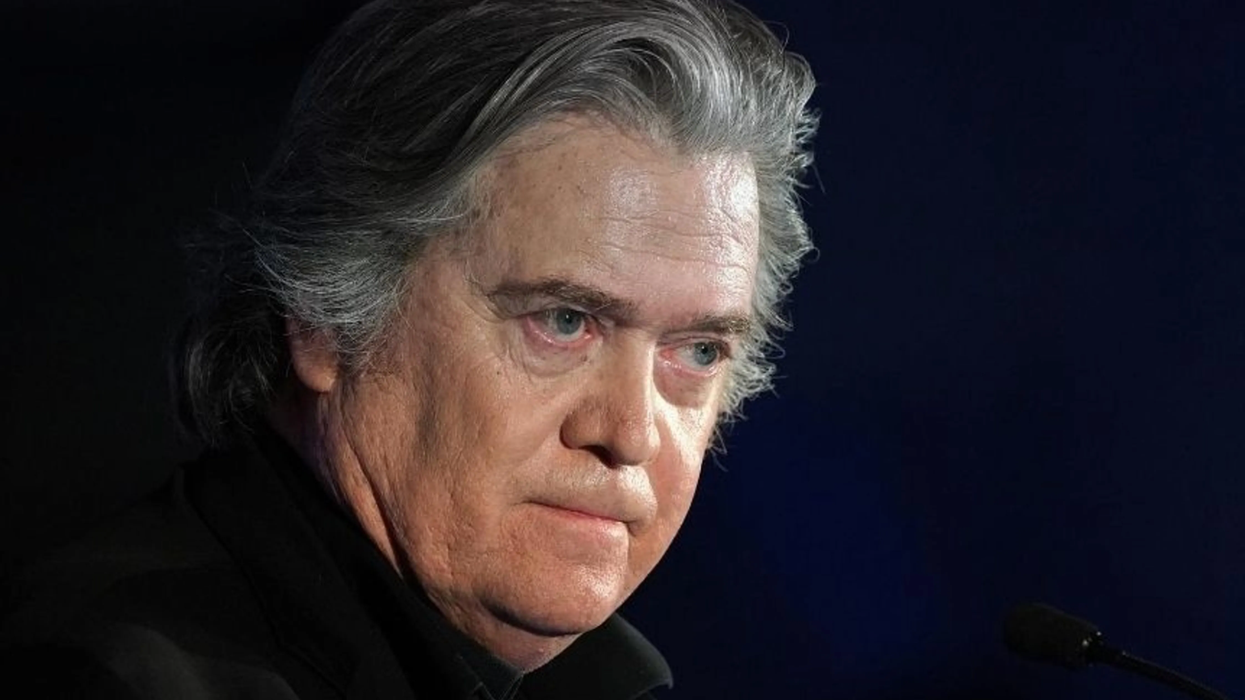

Trump advisor Steve Bannon is facing two counts of contempt of Congress in his upcoming criminal trial for his refusal to appear before the January 6 Committee to testify. Earlier, Bannon defiantly had promised that he would turn the case into a “misdemeanor from hell” for President Joe Biden. Instead, it is looking more like a legal hellscape for Bannon. This comes after a federal judge ruled on Wednesday that evidence concerning Bannon’s primary legal defense—that he was only acting on the advice of counsel—could not even be presented during his trial.

Judge Carl Nichols, who was appointed by President Trump, made that ruling after careful consideration of Bannon’s and the government’s legal arguments. Much of Bannon’s case rested on a series of opinions written by the Office of Legal Counsel at the Department of Justice. Those opinions had stated that, as department policy, advisers to the president are immune from congressional subpoenas on matters related to government business. The opinions separately stated that when a witness’s testimony touches on matters that might implicate executive privilege, the White House is entitled to send a representative to assert executive privilege during the testimony when necessary.

The Justice Department successfully pointed out that these opinions had no bearing on whether Bannon was in contempt for refusing even to appear before the Committee. After all, Bannon could have appeared and pled the Fifth or asserted executive privilege to refuse to answer specific questions. This would have been a risky strategy, however, because so much of Bannon’s communication did not fall under any arguable privilege because they were often made to others besides the former president, and in any event he was not employed at the White House during the relevant time, and the current occupant had waived privilege over communications relating to the insurrection. During oral arguments, the Department stressed that this case was about whether Bannon could simply refuse to appear at all to testify, and that allowing Bannon to hide behind his lawyer’s advice as a defense essentially would obliterate Congressional subpoena power. “The summoned witness doesn’t get to decide if Congress can make them show up,” the Department argued.

Ultimately, Judge Nichols decided that he was bound by existing D.C. Circuit precedent in the case of Licavoli v. U.S., an opinion from 1961 that, while of questionable precedent on other grounds, still held that that refusing to answer a question is not protected by the defense of “following advice of counsel.” All that is needed is that the defendant intended to refuse to answer. “Advice of counsel cannot immunize a deliberate, intentional failure to appear pursuant to a lawful subpoena lawfully served,” the court quoted that opinion as holding.

Some legal commentators saw this as a major defeat for Bannon. “It’s a serious blow, because he doesn’t have another good defense,” Joyce Vance, a former federal prosecutor, said to NBC News. “He’ll now have to make a decision about whether to proceed to trial or try to cut some kind of deal.”

Bannon’s lawyers did not see it as fatal to their case, however, saying that while the ruling prevents them from making a key defense, they could still argue the subpoena itself was invalid and that the entire prosecution is flawed based upon those Office of Legal Counsel opinions. “We believe the prosecution is constitutionally barred and that in any event, the OLC opinions and reliance on them provides a complete defense,” said Bannon’s attorney David Schoen, who intends to move to dismiss the entire case on April 15. If the judge disagrees with Schoen, Bannon will face the prospect of going to trial without any usable defense at all for his actions.

Nichols took some additional interest in the arguments made around executive privilege and the OLC opinions, having himself argued for many years as a Justice Department lawyer in favor of limitations on the subpoena power of Congress against current and former White House officials. If Licavoli were not controlling law in the Circuit, Judge Nichols even mused that he might have come out the other way. But the fact that this particular judge followed the law and ruled against Bannon is significant. With all the district court judges in the Circuit, Nichols actually was among those most likely to be hostile to the Department’s arguments and deferential to former White House advisors, given his history with such cases and his support of the OLC opinions.

But Judge Nichols seems to have drawn a line, based on the Licavoli precedent, that absolute refusal to even show up cannot be shielded by the defense of following advice of counsel. That ruling is likely to be challenged on appeal, but it could be momentous if it is upheld: The Justice Department would then have the current case precedent it needs to more confidently charge others who have now been referred for criminal contempt for their failure to appear, including former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows and, just recently by vote of the House, former advisors Peter Navarro and Dan Scavino.

For more political analysis, subscribe to the Status Kuo newsletter.

@WhiteHouse/X

@WhiteHouse/X

@william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok @william.rath/TikTok

@william.rath/TikTok

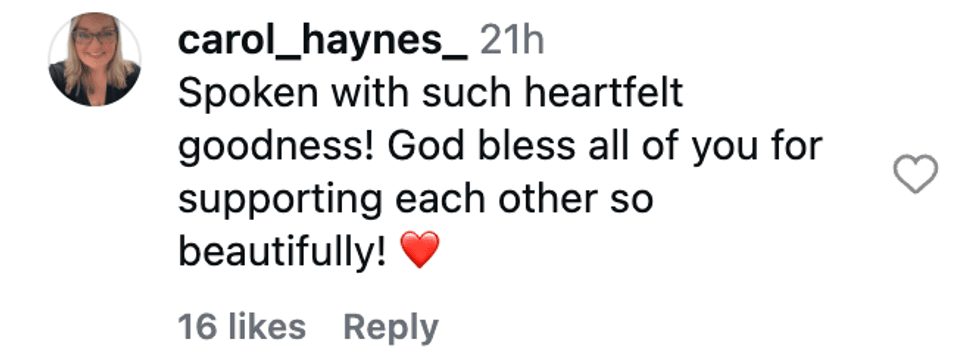

@carol_haynes_/Instagram

@carol_haynes_/Instagram @lwhiteza/Instagram

@lwhiteza/Instagram @iamdrkandace/Instagram

@iamdrkandace/Instagram @solveigerway/Instagram

@solveigerway/Instagram @sziulkow/Instagram

@sziulkow/Instagram @claudiatorres2019/Instagram

@claudiatorres2019/Instagram @carolken/Instagram

@carolken/Instagram @karenpayton34/Instagram

@karenpayton34/Instagram @mamaburnside/Instagram

@mamaburnside/Instagram @alr_thrives/Instagram

@alr_thrives/Instagram @dr.rxq/Instagram

@dr.rxq/Instagram @bogie1954/Instagram

@bogie1954/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram @todayshow/Instagram

@todayshow/Instagram