If Kyle Rittenhouse and his supporters are to be believed, he was a civic-minded kid who drove to defend a town where he'd recently gotten a job, armed himself appropriately given the risks, and shot three men in self-defense out of fear for his own life, two of whom tragically died. He's innocent of the charge of murder because he did what any reasonable person would have done in his situation—and what the law permits.

If the attorneys for Travis McMichael, Gregory McMichael and William "Roddie" Bryan Jr.—the men who killed Ahmaud Arbery—are to be believed, they were making a lawful citizens' arrest of someone they suspected was a burglar after they and several neighbors became concerned about strangers recently seen entering a local property that was under construction. When they followed Arbery in their cars as he jogged and finally trapped him between them, he attacked with his fists and reached for one of their guns, which is when McMichael shot him.

In each case, based on their own statements, the defendants were acting as unofficial armed enforcers of the law. This by itself sets up a potentially violent and chaotic outcome, but the public often sees the facts through the lens of the defendant who is on trial, rather than from the victims who are often deceased or unable to testify. During trial, lawyers zoom in and examine, step-by-step, whether the claim of self-defense was justified in the instance without letting the jury properly consider the larger picture, including the all-important question of what the defendants were doing there in the first place, armed and taking the law into their own hands?

Context winds up mattering a lot in these cases because the state of mind of the victims who fought back often has to be presumed. A teenager armed with an AR-15 assault rifle conjures images of mass school shootings, for example. This would be a cut-and-dried case if Rittenhouse had walked onto a school grounds armed like that and killed someone who had tried to tackle him and take away his gun. He wouldn't be able to claim self-defense if he had shot a "good guy with a gun" who had fired upon him first in order to try to save children's lives. We would say that Rittenhouse "provoked" this in the first instance by entering school grounds armed with an assault weapon.

Similarly, if the killers of Ahmaud Arbery were wearing hoods and flying confederate flags from their pick-up trucks, even the nearly all-white jury in Brunswick, Georgia likely would conclude that Arbery had reason to fear for his life and that the men had provoked him to attack and reach for one of their guns. After all, he was one unarmed Black man who was "trapped like a rat" (to use Greg McMichael's own words to the police) facing three armed white men clearly bent on doing him serious harm or killing him. The jury probably would conclude these men had provoked the very act that they now claim they needed to stop out of "self-defense."

Provocation is an exception to self-defense in most jurisdictions, but its strength varies greatly. Wisconsin, for example, defines the provocation exception this way:

(2) Provocation affects the privilege of self-defense as follows:

(a) A person who engages in unlawful conduct of a type likely to provoke others to attack him or her and thereby does provoke an attack is not entitled to claim the privilege of self-defense against such attack, except when the attack which ensues is of a type causing the person engaging in the unlawful conduct to reasonably believe that he or she is in imminent danger of death or great bodily harm. In such a case, the person engaging in the unlawful conduct is privileged to act in self-defense, but the person is not privileged to resort to the use of force intended or likely to cause death to the person's assailant unless the person reasonably believes he or she has exhausted every other reasonable means to escape from or otherwise avoid death or great bodily harm at the hands of his or her assailant.

Under this definition, Rittenhouse can pretty easily argue that if he did provoke the attack, it doesn't matter because the victims came at him with deadly force and the provocation exception to self-defense is undone by that. After all, one victim carrying a chain even threatened to kill him and threw a plastic bag at him (one he thought was a weapon), and another victim struck him in the neck with a skateboard and tried to grab his gun. He had no choice but to shoot, right?

But now wait, Rittenhouse was already deemed by others to be an active shooter after he killed the first victim. So what should other ordinary citizens have done here? Isn't it reasonable (and even right, according to those who champion "good guys with guns") for them to take every step they can to stop him from shooting more people?

Context matters. Rittenhouse was a teenager out on the streets after curfew armed with an assault weapon. He had just shot someone dead in the middle of an explosive riot. We come back to the question, "What was he doing there in the first place?" Again, we would certainly ask that question if Rittenhouse had entered a high school with an AR-15. In fact, we would presume he was there to commit murder, even if he later claimed he was there only to protect the school from other shooters. And there can be little doubt that the police would have stopped, if not gunned down, any Black man seen out that night after curfew in the midst of the Kenosha riots while brandishing an AR-15.

Arbery's killers are another example of the system gone amok, one that operates to shield armed vigilantes from legal consequences. Was Arbery expected not to fight back against a clear threat to his person from three armed men stalking him in their trucks? Does his act of trying to save his own life excuse them on grounds of self-defense? At some point, we have to conclude that the provoking itself is to blame. We might indeed conclude that, had Rittenhouse and the McMichaels not acted the way they did initially by carrying weapons and taking the law into their own hands, the whole violent situation would have never begun.

Of course, the public also knows things that the jury doesn't and probably won't get to hear, such as that Rittenhouse was recorded weeks earlier saying he wished he had his "f-cking AR" to shoot looters who were leaving a CVS, and that the press reported that Gregory McMichaels used racial slurs in text messages and on social media and even uttered another racial slur after blasting Arbery three times with a shotgun. These would help answer the contextual question, "What was he doing there in the first place?" This evidence suggests strongly they weren't really there to help. Rather, they were itching for an opportunity to use their weapons.

Our legal system isn't set up well to understand "provocation" through a larger societal lens even though citizens already understand it well. Schools, movie theaters, racially charged protests—these are places you can't bring an AR-15 without people presuming, and reasonably so, that you are looking to murder others. Similarly, three white men can't stalk a lone minority jogger from their trucks and point shotguns at him without him presuming, and reasonably so, that his own life is in danger.

The law should be rewritten to ensure this outright. It should deter people from carrying AR-15s into hot zones after curfew. It should dissuade vigilantes from Gregory McMichaels to George Zimmerman from thinking they can stalk, terrorize and shoot at lone Black men or boys who are just out for a walk or a jog. (By the way, this is a good example of how Critical Race Theory, which asks that we examine our legal system from the point of view and stories of the oppressed minorities, actually can play a part in the reform of our laws and justice system.)

Reasonable actions taken by others against an armed and presumably dangerous individual—one who has no business being there—should not be grounds for a claim of "self-defense" in any fair legal system. This question will rise in importance as more states relax open carry laws. The provocation exception simply remains far too narrow, and the right to "self-defense" too wide, to account for these increasingly common and often racially-charged vigilante attacks and killings.

@obamaatredrobin/X

@obamaatredrobin/X

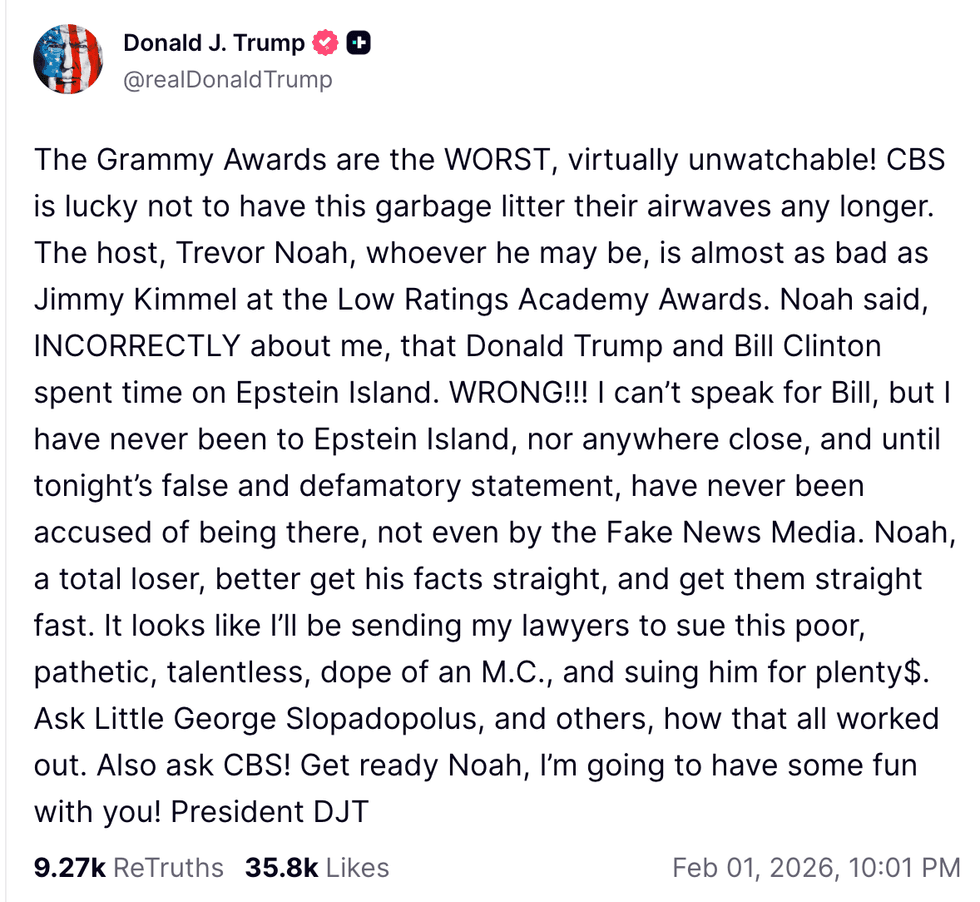

@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social

@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social

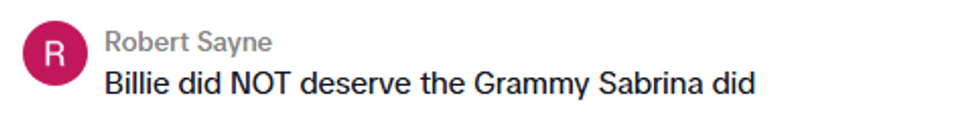

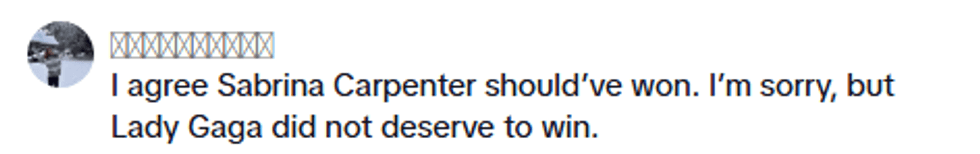

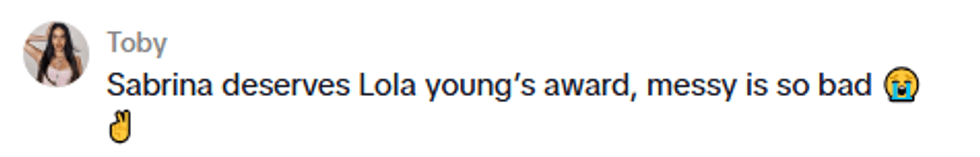

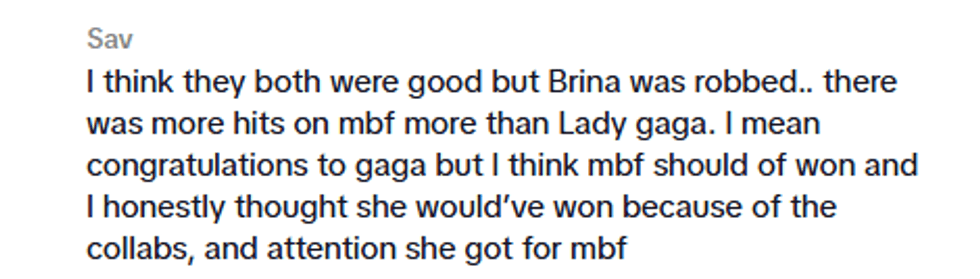

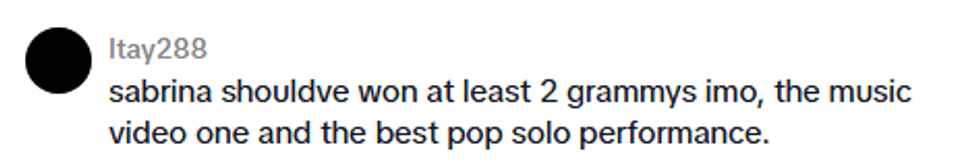

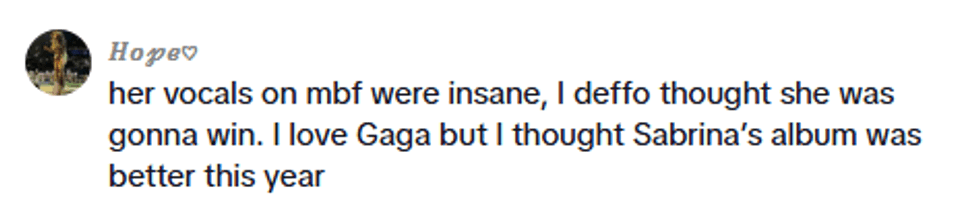

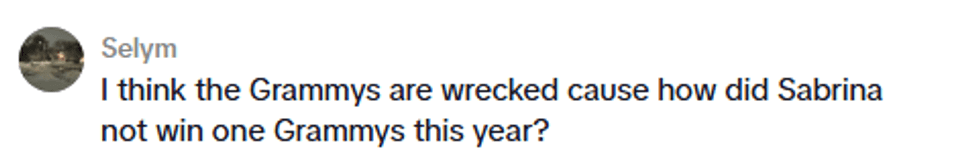

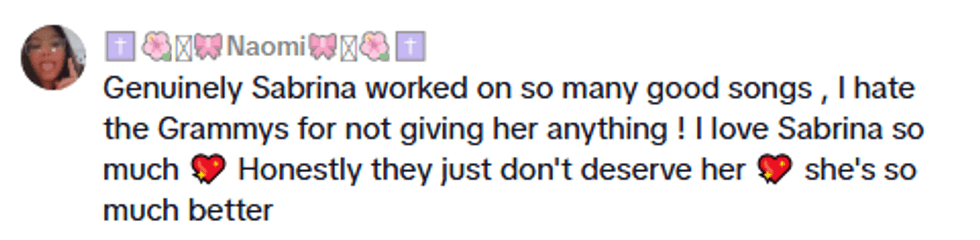

@.a.zan/TikTok

@.a.zan/TikTok @.a.zan/TikTok

@.a.zan/TikTok @.a.zan/TikTok

@.a.zan/TikTok @.a.zan/TikTok

@.a.zan/TikTok @.a.zan/TikTok

@.a.zan/TikTok @.a.zan/TikTok

@.a.zan/TikTok @.a.zan/TikTok

@.a.zan/TikTok @.a.zan/TikTok

@.a.zan/TikTok @.a.zan/TikTok

@.a.zan/TikTok @.a.zan/TikTok

@.a.zan/TikTok @.a.zan/TikTok

@.a.zan/TikTok @.a.zan/TikTok

@.a.zan/TikTok @.a.zan/TikTok

@.a.zan/TikTok @.a.zan/TikTok

@.a.zan/TikTok @.a.zan/TikTok

@.a.zan/TikTok