Humanity’s consumption of drugs is making its way down the food chain. Prescription drugs ranging from antidepressants, blood thinners, erectile dysfunction drugs and birth control pills to illegal drugs like cocaine and methamphetamine are working their way through human bodies and plumbing systems and into lakes, rivers, and oceans, where they are affecting fish and other wildlife. Eventually, they make their way up the food chain and return to us via the plants and animals we eat. Their impact on human health remains unclear, but some scientists are finding troubling impacts on aquatic life.

“We have every reason to suspect that the release of stimulants to aquatic environments is on the rise across the globe, yet little is known about the ecological consequences of this pollution,” said Emma Rosi-Marshall, a freshwater ecologist at the Cary Institute.

In New Zealand, testing at wastewater treatment plants found high concentrations of methamphetamine. “The testing identifies a number of different drugs that are metabolized by the body, and it tells us objectively that we have a high use of methamphetamine in Northland,” said Ian McKenzie from Northland DHB.

Opioids are accumulating in Puget Sound shellfish. Samples from Bremerton's Sinclair Inlet and Seattle's Elliott Bay revealed oxycodone, antibiotics, antidepressants, and high levels of Melphalan, a chemotherapy drug, according to researchers with the state Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Puget Sound Institute at University of Washington-Tacoma.

"It's a reminder that what we consume on land winds up in the waters of Puget Sound," said biologist Jennifer Lanksbury.

In Europe, scientists have determined that the critically endangered European eel has a cocaine problem. According to a study published in Science of the Total Environment, eels exposed to cocaine through rising concentrations of the drug in waterways show dramatic physical and behavioral changes. The drug accumulates in the brain, muscles, gills, skin and other tissues of the eels. The muscle of the fish also showed swelling and breakdowns, and the hormones that regulate their physiology changed.

“Data show a great presence of illicit drugs and their metabolites in surface waters worldwide,” says Anna Capaldo, a research biologist at the University of Naples Federico II and the lead author of the study. She noted that water near densely populated cities is even worse; another study found particularly high concentrations in the London’s Thames River near the Houses of Parliament and in Italy’s Amo River near Pisa.

So what happens when eels do drugs? For 50 days, the scientists exposed the creatures to the same amount of the drug they are exposed to in the wild via drug-polluted waterways. They then created a 10-day “rehab period” in which the researchers removed the eels from water with cocaine. Even after rehab, the eels demonstrated elevated cortisol and dopamine levels. Muscle condition remained impacted. The eels travel to the Sargasso Sea to reproduce, but if their muscles are impaired and they cannot build up enough fat reserves for the long journey, that process is jeopardized. “All the main functions of these animals could be altered,” Capaldo says. “It is likely that in this condition, the reproduction of the eels could be impaired.”

Reproductive health is a critical concern for sensitive aquatic species. In the United States, populations of largemouth bass are becoming intersex due to exposure to pharmaceuticals and other waterborne pollutants. At a study of 16 sites, including Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, West Virginia, Pennsylvania and in the Columbia, Colorado and Mississippi river basins, male fish were being found with eggs in their testes. “We found female germ cells in the testes of 82 percent to 100 percent of the male smallmouth bass and in 23 percent of the largemouth bass,” the agency said. At one polluted site in the Susquehanna near Hershey, Pa., 100 percent of male smallmouth bass that were sampled had eggs. In another study, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service surveyed fish in the upper Potomac River and its tributaries, including the Shenandoah River.

“When fish are getting intersex, it’s probably a good indication that something is wrong in the environment,” says Vicki Blazer, a researcher at the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Fish Health Research Laboratory in West Virginia.

Studies have shown that even low concentrations of drugs in the environment can change the bacterial or algal communities in water, affect the growth rate and life cycles of insects, and affect predator-prey interactions. The drug use of humans at the top of the food chain trickles all the way down to the organisms like the moss, insects and aquatic bacteria that is food for birds, fish, and amphibians—including species that humans eat. Over time, as more and more drugs enter the system, it becomes more difficult for waterways to dilute their impact.

In the United States alone, people fill 3.7 billion prescriptions a year, and then either excrete the drugs into the wastewater system or flush unused medication down the toilet. Drugs are used on a larger scale in livestock production. What can be done to minimize their impact? Not much. Most wastewater treatment systems are not equipped with the technologies needed to filter out drugs before discharging water back into the environments. Scientists urge people to turn unused drugs in to pharmacies, where they can be disposed of safely. But individual users are only part of the problem.

The manufacturing facilities that produce drugs discharge pharmaceutical contaminants into water systems at much higher concentrations. A national study examining pharmaceutical manufacturer wastewater found 33 drugs in substantially higher concentrations in waters near industrial pharmaceutical plants, and concluded that drug companies “are an important, national-scale source of pharmaceuticals to the environment.”

“All of these pharmaceuticals, and almost every emerging contaminant that we are looking at these days are not regulated,” said Tia-Marie Scott, lead author of the study and physical scientist for the USGS. “There are no thresholds for what is and what is not considered safe.”

In Europe, concern is rising that pharmaceutical plant discharge could lead to microbial resistance in humans. The German Energy and Water Association (BDEW) says the total quantity of medicinal drugs for human use would rise by 68.5% by 2045. A report commissioned by the British government estimated that 700,000 deaths globally could be attributed to AMR in 2015 and that the annual toll would climb to 10 million deaths in the next 35 years.

In April 2018, five organizations—European Environmental Bureau, Changing Markets Foundation, Health Care Without Harm Europe, and Pesticides Action Network—signed a joint letter asking for policy changes to deal with the growing threat drugs pose to the ecosystem. “We are concerned that the pharmaceutical industry is currently excluded from any kind of environmental legislation, which is untenable in the light of the risk that pharmaceutical pollution poses to the environment and to human health,” the signees said, noting that as human drug consumption rises and concentrations of pharmaceuticals rise, the impacts will grow if measures—including changes to wastewater treatment methods and regulations on discharge into the environment— aren’t taken now.

In other words, the canary in the coal mine is now the fish in the waterway.

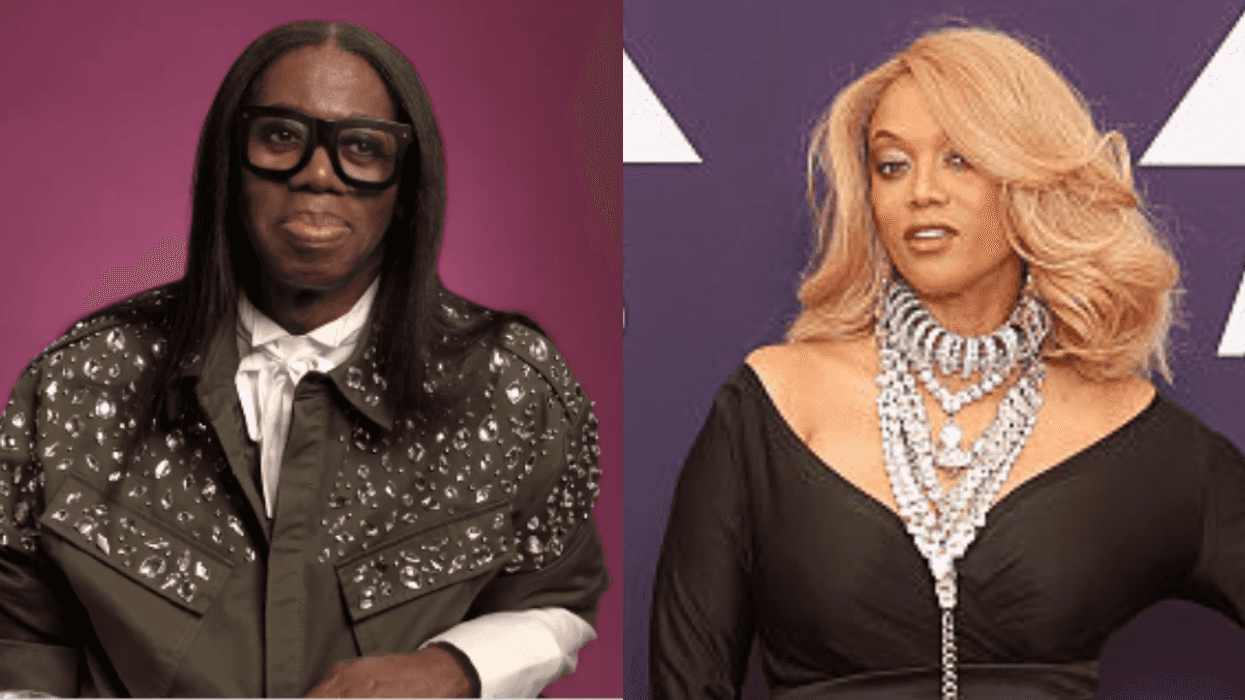

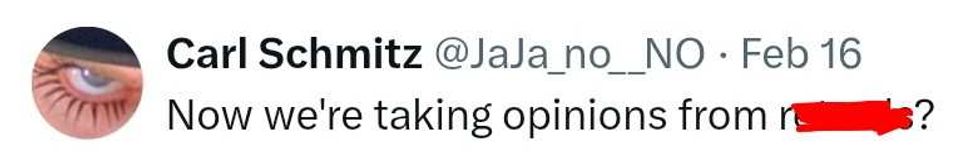

@JaJa_no_NO/X

@JaJa_no_NO/X @CWMorgan1000/X

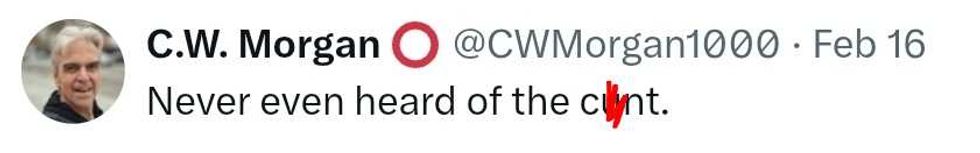

@CWMorgan1000/X reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram