Three years after China began its campaign against the coronavirus and adopted a “Zero-Covid” policy, the government’s extreme measures—draconian lockdowns, economic disruption, and now deaths resulting from its prevention measures—are facing significant public protest and pushback.

It is rare in China to witness protests, particularly around a unifying grievance, crop up in multiple spots around the country. And it is even rarer, and quite dangerous, for anyone to criticize Chinese leaders directly and by name.

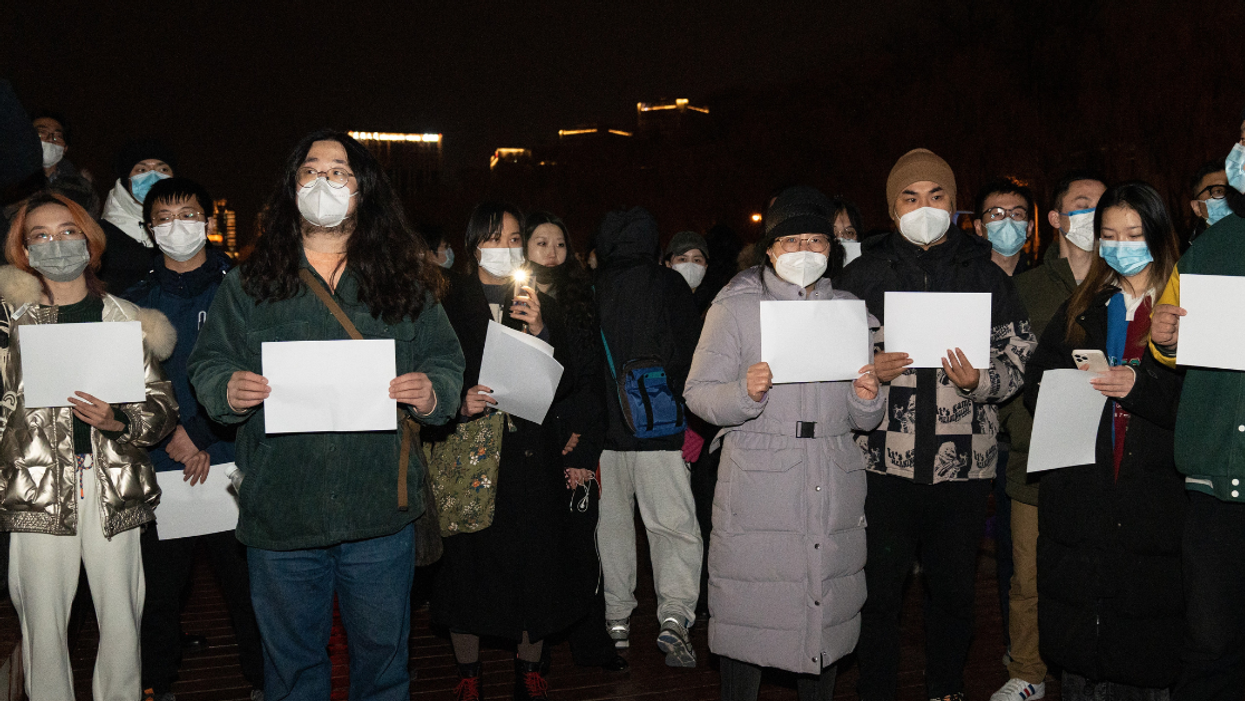

Yet in major cities and universities across China, protestors holding blank white pages—a stark symbol of censorship—have erupted in the past two days over the nation’s harsh Covid policies. To the alarm of the government, the protestors also have called for greater democratic freedoms and even for China’s President, Xi Jinping, to step down.

This is raising fears in party leadership that a contagion of opposition could spread and wreak even more havoc than the virus. Should the protests grow in size or intensity, the government likely will crack down, perhaps severely, citing the need for public order during a still unresolved pandemic.

Origins of the Unrest

China has seen a surge in new Covid cases numbering in the tens of thousands, which is high by Chinese standards. That has led local officials to impose another series of lockdowns, leading to widespread complaints and suggesting to many Chinese that the government does not have the capability to both control the virus and keep the economy open and strong.

Last Friday, a fire in an apartment building in Urumqi, the capital of China’s restive Xinjiang Province, led to 10 deaths and nine injuries. Parts of Urumqi have been in Covid lockdown for some 100 days, and there were unconfirmed reports, accompanied by viral videos on TikTok, that the victims of the fire were actually locked in their homes and couldn’t escape the flames—a charge the government denies.

The incident follows other tragedies, including a bus accident earlier this fall in Guizhou Province in which 27 people who were being taken to quarantine were killed. Many pointed out that the cost in lives of the quarantine measures exceeded the number of deaths, at least so far, from the virus.

The incident also threatened to become a rallying cry for protests against the Zero-Covid policy of the government until online posts about it were shut down.

Anti-lockdown protests turned violent just last week in the city of Zhengzhou at the Foxconn facility, which is the world’s largest iPhone factory. Workers were angry at the terms of their employment contracts, which included covid-related terms governing their living conditions.

Videos of the protests circulated widely on social media. The demands of the workers captured a national sense of frustration at the government’s policies and set the stage for the deadly fire in Urumqi to become a tipping point.

Pressure also came from another unlikely source: footage of the World Cup, where fans in the stadium and around the world were seen gathered and celebrating their teams, but without masks or social distancing.

China’s censors acted quickly to edit footage of maskless fans at the games, but this only added to the collective sense that the Chinese government’s policies have failed.

From its less-effective vaccine and low rates of vaccination among at-risk groups, particularly the elderly, to its inability after three years to prepare China’s medical system for a crush of cases, the government now faces a hard reckoning.

While the rest of the world has moved on and is enjoying relative freedom and normalcy, China feels stuck in 2020 with its lockdowns and quarantines.

As videos of protests in Shanghai, Beijing and other cities against the government began circulating online, steps ahead of the government censors and in direct defiance of the Chinese leadership, other protests quickly broke out in smaller cities.

Whether the protests will peter out or galvanize into a broader movement and problems for the government, as they did recently in Iran, remains unclear. As of Monday, foreign media has reported increased police presence on the streets of major cities and no signs of new protests in Beijing and Shanghai.

Echoes of Protests Past?

The largest protest so far appears to have taken place in Shanghai at the intersection of Urumqi road, in honor of the people who lost their lives in the fire in that city. The blank white papers held by the protestors evoked a dual symbolism: the lack of words representing the denial of freedom of speech and the white evoking a traditional funeral color.

Chinese leaders well understand the power of public mourning in the country and the risk it poses to their rule. The Tiananmen protests of 1989 were sparked by the death of a reformer in the party, former general secretary Hu Yaobang, who was forced to step down due to his liberal market policies.

Hu passed away the week before the protests began. Then, some 100,000 students marched to the square a day ahead of his funeral, sparking the beginning of the takeover of the square.

The current unrest doesn’t come close to the scale and ultimate tragedy of that protest movement. But the Covid protests are notable because they mark the first time since 1989 that the country has seen any kind of widespread public opposition to official policy and CCP rule.

The connectivity of the people via social media, messaging apps, and cellphones also means that the risk of the unrest spreading, via unofficial news and video clips of other activity around the country, is far higher than it was in 1989.

Losing The Mandate of Heaven

Chinese leaders may have the weight of Chinese history and culture on their minds as they deal with protests. Through over three thousand five hundred years of Chinese civilization, dynasties have ruled by claiming a “Mandate of Heaven” that justified their authority.

At risk of oversimplification, that Mandate meant the leaders enjoyed the backing of the gods, something like the “divine right of kings” in European history. But the Mandate came with some conditions as part of the deal.

Importantly, the Mandate meant that the emperor was responsible for the well-being of the Chinese people. If poor governance resulted from his rule, the divine authority to govern could be withdrawn by Heaven.

There were usually telltale signs of poor performance: natural disasters, droughts, famines, and yes, pandemics. One of the underlying reasons for the strict Zero-Covid policy may be tied culturally to the idea that the leaders must at least keep the people safe from a deadly plague.

While the CCP’s revolution in 199 was intended to break the hold on feudalistic and traditional thinking, it isn’t so easy to escape the pull of cultural gravity. Widespread rebellions by peasants traditionally have served as evidence that the emperor no longer enjoys the support of Heaven.

That remains an important backdrop for why it is likely that the party will crack down heavily on any continued protests, long before they spread and wind up confirming in the minds of the Chinese people that its leaders have lost their right or ability to rule.

There is something of a grand bargain at work here, too. After the deadly suppression of the Tiananmen protests in 1989, China embarked on a path of market reforms even while clamping down on democratic rights.

The Chinese people largely came to accept their loss of certain freedoms in exchange for stability, economic growth and prosperity. But now that grand bargain is being eroded, and many can see for themselves that the rest of the world has moved on from the pandemic while China has not.

This places Xi Jinping and party leadership in a difficult bind. China has yet to go through the trauma of widespread contagion and death from the virus, and its medical systems and less effective vaccines aren’t prepared for the potential chaos and misery that might result. Because of this, the government’s hands remain tied.

Yet if it continues to impose its harsh policies, it risks widespread protests and defiance, especially from young people who aren’t as likely to be affected by the disease but whose economic and life prospects are being eroded daily.

It now appears that the government will attempt to walk a tight wire by easing rules around Covid restrictions, even while reaffirming its Zero-Covid policy.

For example, in response to the recent protests, Beijing authorities announced on Monday that they would no longer set up gates to block access to apartment compounds where infections are found. In the city of Guangzhou, a hotspot in the last wave of infections in China, the government announced some residents will no longer have to undergo mass testing, citing a need to conserve resources.

But as case numbers rise as a result of eased restrictions, it is unclear how the government can realistically maintain a Zero-Covid policy without the kinds of lockdowns and restrictions it has imposed in the past.

If protests reignite in response to more lockdowns or quarantine incidents, China could face both crises at once: an explosion in cases and deaths and widespread unrest and protests directed in anger at Chinese leadership.

Instability at that level, affecting the second largest economy, would have far reaching consequences for the entire world.

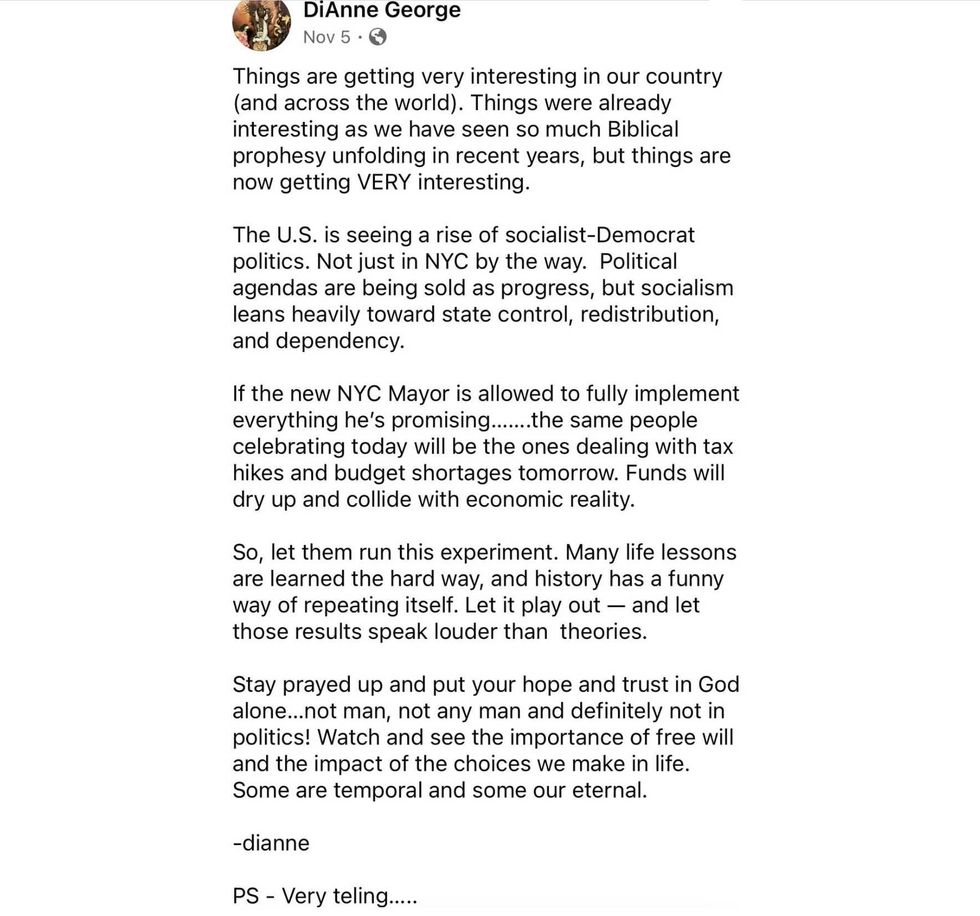

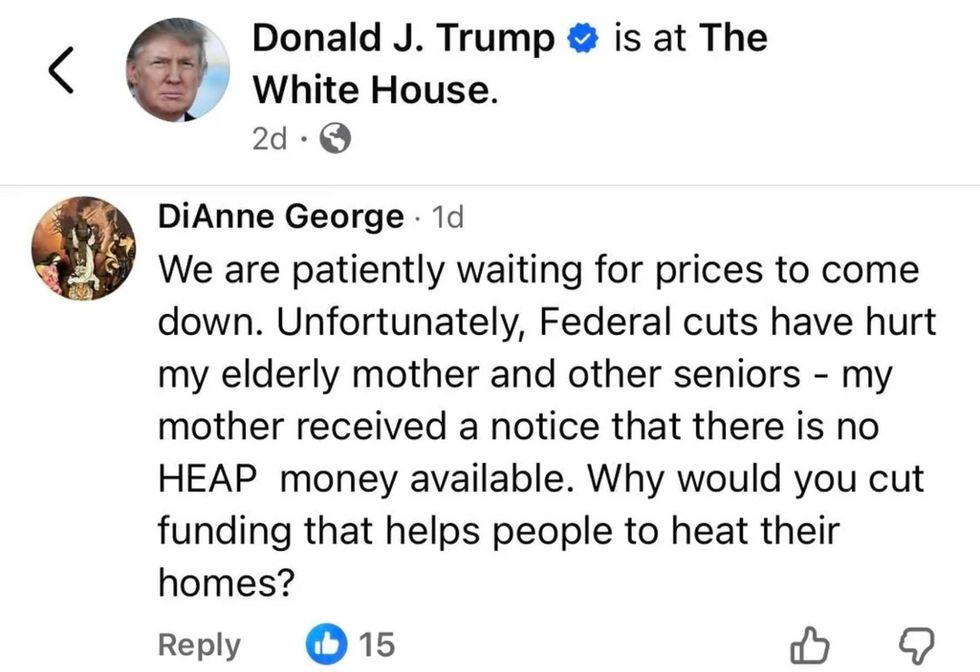

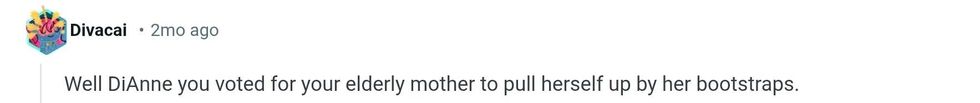

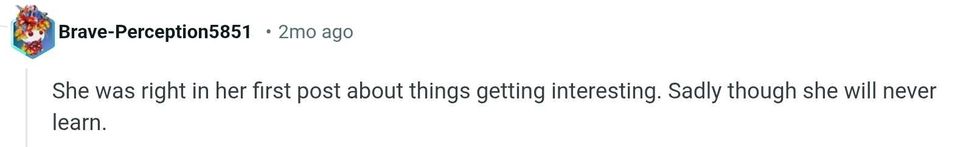

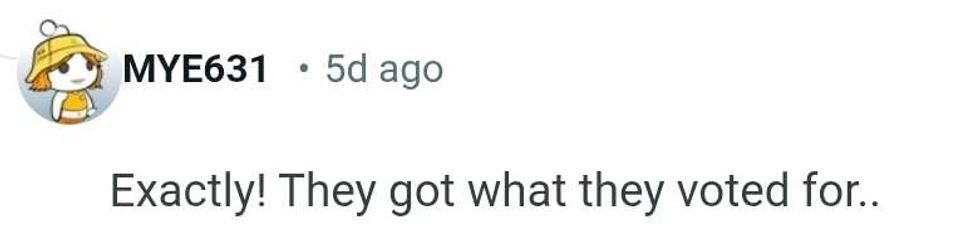

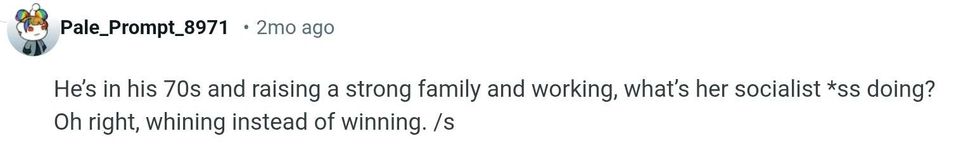

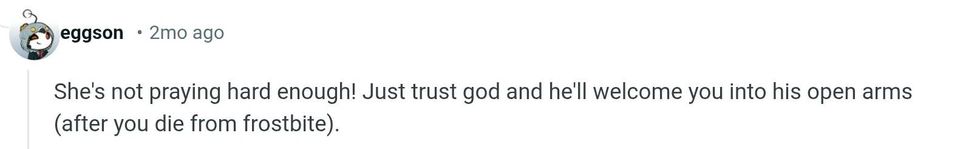

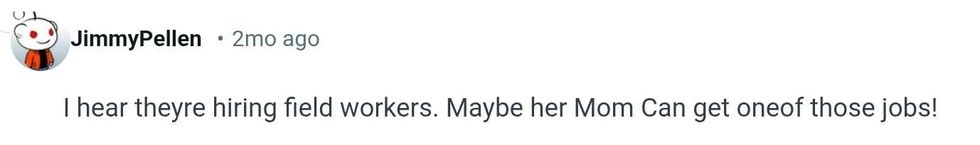

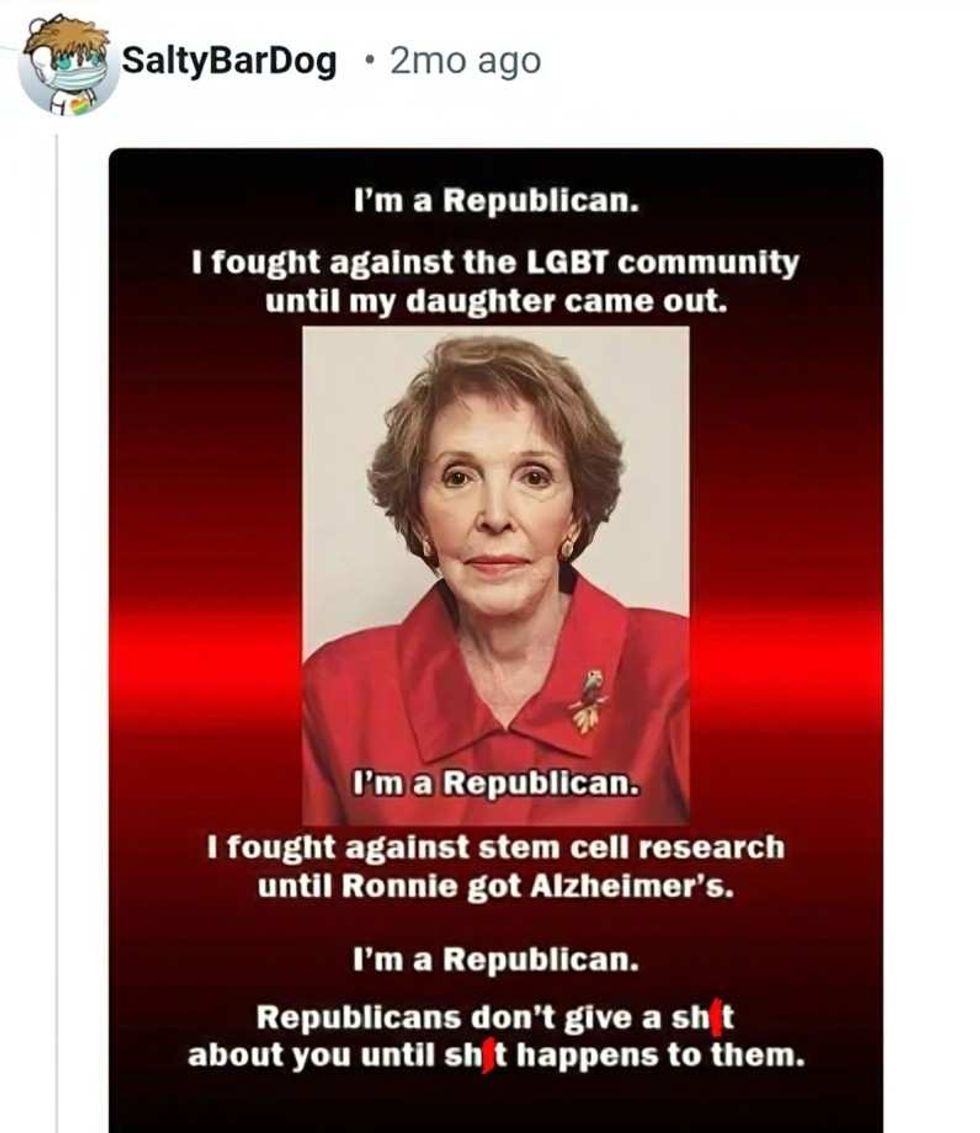

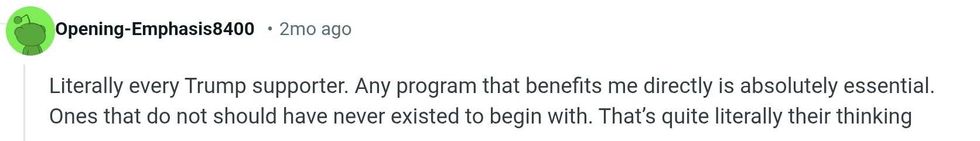

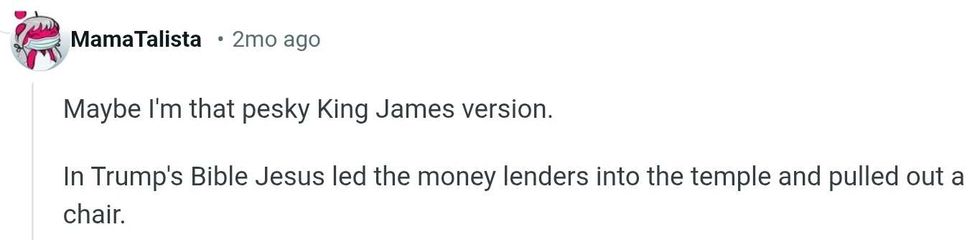

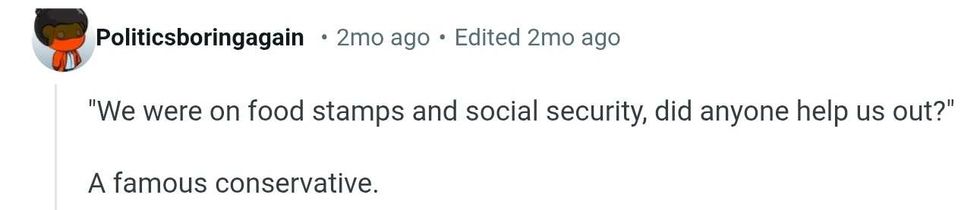

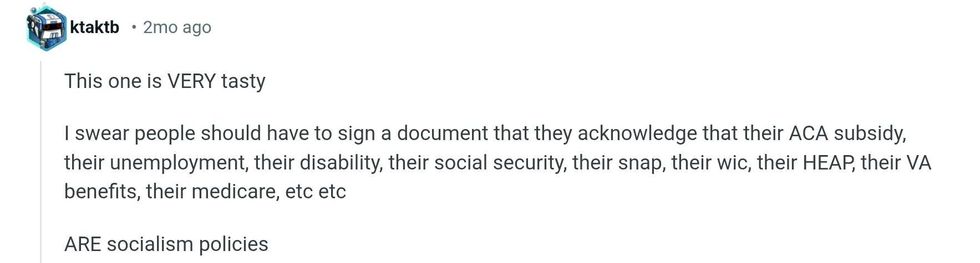

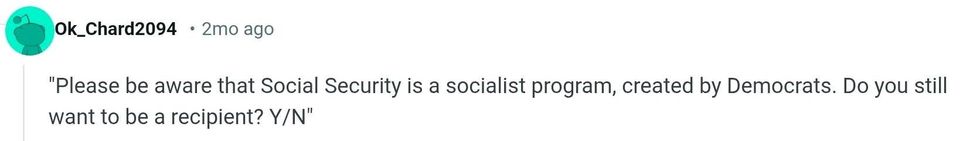

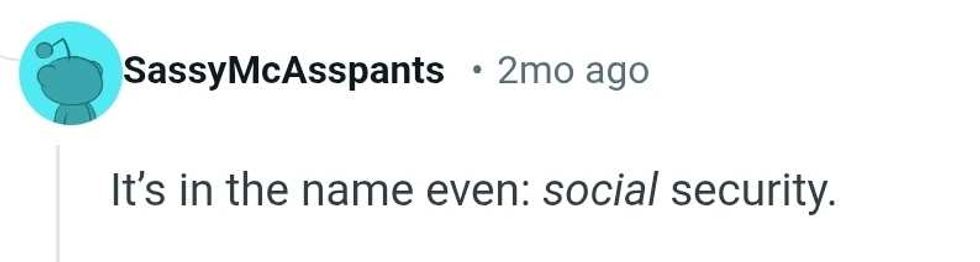

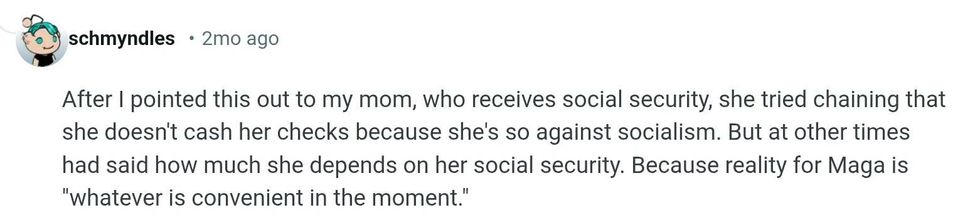

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

@meidastouch/X

@meidastouch/X @meidastouch/X

@meidastouch/X @meidastouch/X

@meidastouch/X @meidastouch/X

@meidastouch/X

illustrate margot robbie GIF

illustrate margot robbie GIF

Bbc One Love GIF by BBC Three

Bbc One Love GIF by BBC Three  Oh Yeah Dancing GIF by Jennifer Accomando

Oh Yeah Dancing GIF by Jennifer Accomando