The GOP has a big political problem, and it knows it.

Having initially agreed to defer to the House Committee on Homeland Security for the creation of a bipartisan commission to investigate the insurrection of January 6, Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) found himself backpedaling fast over the course of the week. He likely assumed Democrats would never agree to the GOP's demands, which included a requirement that any subpoena issued by the Commission receive approval by both the Chair and the Vice-Chair or a majority of votes from the evenly divided, 10-person Commission. He concluded that this would doom the notion of a bipartisan effort to get at the truth.

It turned out that the ranking GOP member of the committee, John Katko (R-NY), was able to reach quick agreement with Committee Chair Bennie Thompson (D-MS) on the formation of the Commission. As a bipartisan body, five of the commissioners, including the Chair, would be appointed by the Speaker of the House and Majority Leader of the Senate, while five commissioners, including the Vice Chair, would be appointed by the Minority Leaders of the House and Senate. Each commissioner would possess significant expertise in law enforcement, civil rights, civil liberties, privacy, intelligence, and cybersecurity. Current government officers or employees were prohibited from appointment.

The speed at which the deal came together appeared to surprise McCarthy. Indeed, it's not clear what McCarthy's thinking here was, given that Katko was one of the House members who joined the Democrats in voting to impeach the former president.

Meanwhile, former president Trump began to rail from Mar-a-Lago against the Commission.

He said in a statement on Monday night.

"Republicans in the House and Senate should not approve the Democrat trap of the January 6 Commission. Republicans must get much tougher and much smarter, and stop being used by the Radical Left. Hopefully, Mitch McConnell and Kevin McCarthy are listening!"

This put McCarthy in the very awkward position of having to renege on the deal even after all his stated demands had been met. After first indicating he would not pressure members for a "no" vote, he changed his mind. He and House Minority Whip Steve Scalise began to round up votes to block the bill. Still, this effort failed; the bill passed the House with surprising levels of support from the GOP, with a full 35 Republican members signing on to it.

On Thursday, Trump released another angry statement condemning the "35 wayward Republicans" in the House who had voted for the creation of the Commission and threatening voter retribution. "Democrats stick together, the Republicans don't. They don't have the Romney's [sic], Little Ben Sasse's [sic], and Cheney's [sic] of the world. Unfortunately, we do," he said. "Sometimes there are consequences to being ineffective and weak. The voters understand!"

The fate of the bill in the Senate remains as unclear as Minority Leader Mitch McConnell's position on it had been. As a bill coming under regular order, it is subject to the normal procedural rules in the Senate, which means the GOP could filibuster it. McConnell, who once condemned Trump's role in the insurrection by saying the "mob was fed lies" and "were provoked by the president and other powerful people," at first claimed he was undecided on the Commission but then a day later (following Trump's statement) came out forcibly against it, calling it "slanted and unbalanced."

McConnell knows that a Commission such as this would shine a spotlight on the former president's role in inciting his followers to riot, as well as likely ensnare several GOP House members and perhaps a GOP senator or two in charges of conspiracy—or at least paint them as sympathetic to the violence and to the rioters. That could cost the GOP critical votes in 2022, when they hope to retake both chambers of Congress. His desire for political power once again appears to override any sense of loyalty to the country's security or respect for the truth.

If McConnell is successful at blocking the bill in the Senate, however, this isn't the end of the story. Democrats have at least three options they can still deploy, none of which are very palatable to the GOP.

Speaker Pelosi has already warned that if the bill does not pass the Senate, she could set up a Select Committee, comprising primarily Democrats, to conduct the investigation. "If they don't want to do this," Pelosi said, "we will find the truth." The GOP had deployed a partisan Select Committee to investigate Benghazi for years, keeping it in the spotlight with a constant negative press drumbeat for Secretary Clinton. There is nothing to stop Pelosi from doing the same here to Trump and his insurrection acolytes.

Speaker Pelosi could also ramp up Committee hearings in Congress even while the Justice Department continues its work, looking into, for example, how social media, conspiracy theories, and election disinformation metastasized into insurrection. These hearings would proceed even as prosecutors continue arresting and charging hundreds of rioters with likely charges of sedition coming against their leaders. The optics of Congressional hearings alongside high-profile criminal trials that are likely to implicate the political allies of the defendants can't be good for the GOP or its prospects in 2022.

A third option is the appointment of a Special Counsel. Special Counsel appointments make sense when the risk of conflicts of interest or politicization of an investigation runs high. Here, the reason Republican leadership opposes even a bipartisan commission is because members of their own caucus, or even the former president and his advisers, may be deeply implicated by its findings. Because any investigation by Merrick Garland's Department of Justice directly into the involvement of the GOP or the former president could raise cries of partisan motivations, the appointment of an independent Special Counsel could blunt the appearance of political goals or pressure. And a Special Counsel also could subpoena witnesses and documents without having to seek bipartisan agreement that could turn the process into a circus.

Many Democrats are wary of going the Special Counsel route, having been stung by the weak results of the Mueller investigation. But Mueller's work and findings were kneecapped by Bill Barr and Trump's Department of Justice itself, which went into the process with a foregone conclusion of not charging the former president if there were any way not to. That is unlikely in the extreme to happen here.

Further, the very threat of an appointment of a Special Counsel—should a bipartisan commission fail to receive enough support from GOP senators—might be enough to win over a few votes in the Senate. Seven GOP senators voted to convict Trump at the impeachment trial, and the unexpectedly high GOP House support for the bill could give much needed political cover, so a filibuster-proof supermajority in the Senate is still within the realm of the possible.

In short, perhaps all the senators need is a bit of encouragement to pass the bill. A bipartisan commission suddenly might sound a lot better than a Select Committee of mostly Democrats, a multitude of House hearings, or an independent Special Counsel with broad subpoena powers.

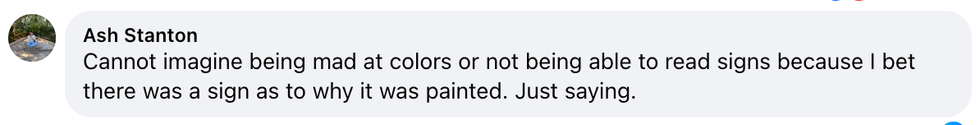

Ash Stanton/Facebook

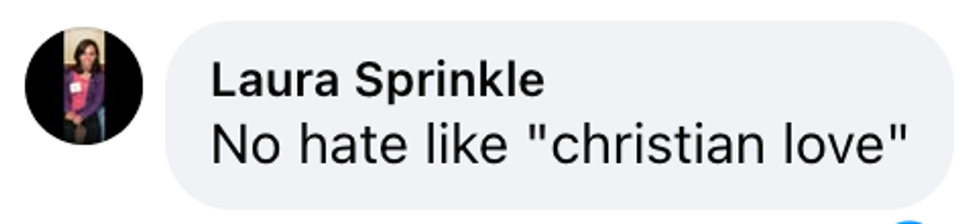

Ash Stanton/Facebook Laura Sprinkle/Facebook

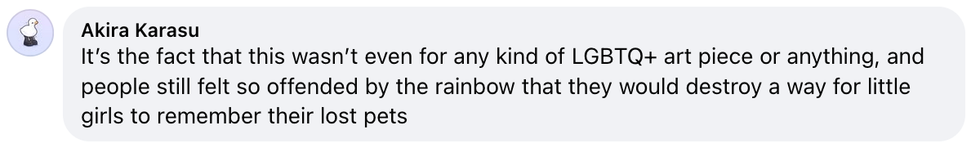

Laura Sprinkle/Facebook Akira Karasu/Facebook

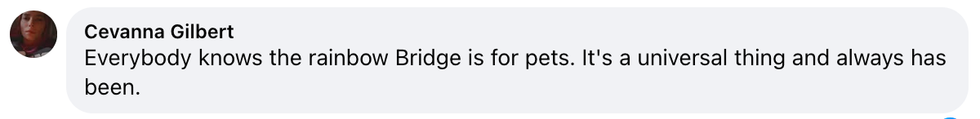

Akira Karasu/Facebook Cevanna Gilbert/Facebook

Cevanna Gilbert/Facebook Troy Adam/Facebook

Troy Adam/Facebook

@GovPressOffice/X

@GovPressOffice/X

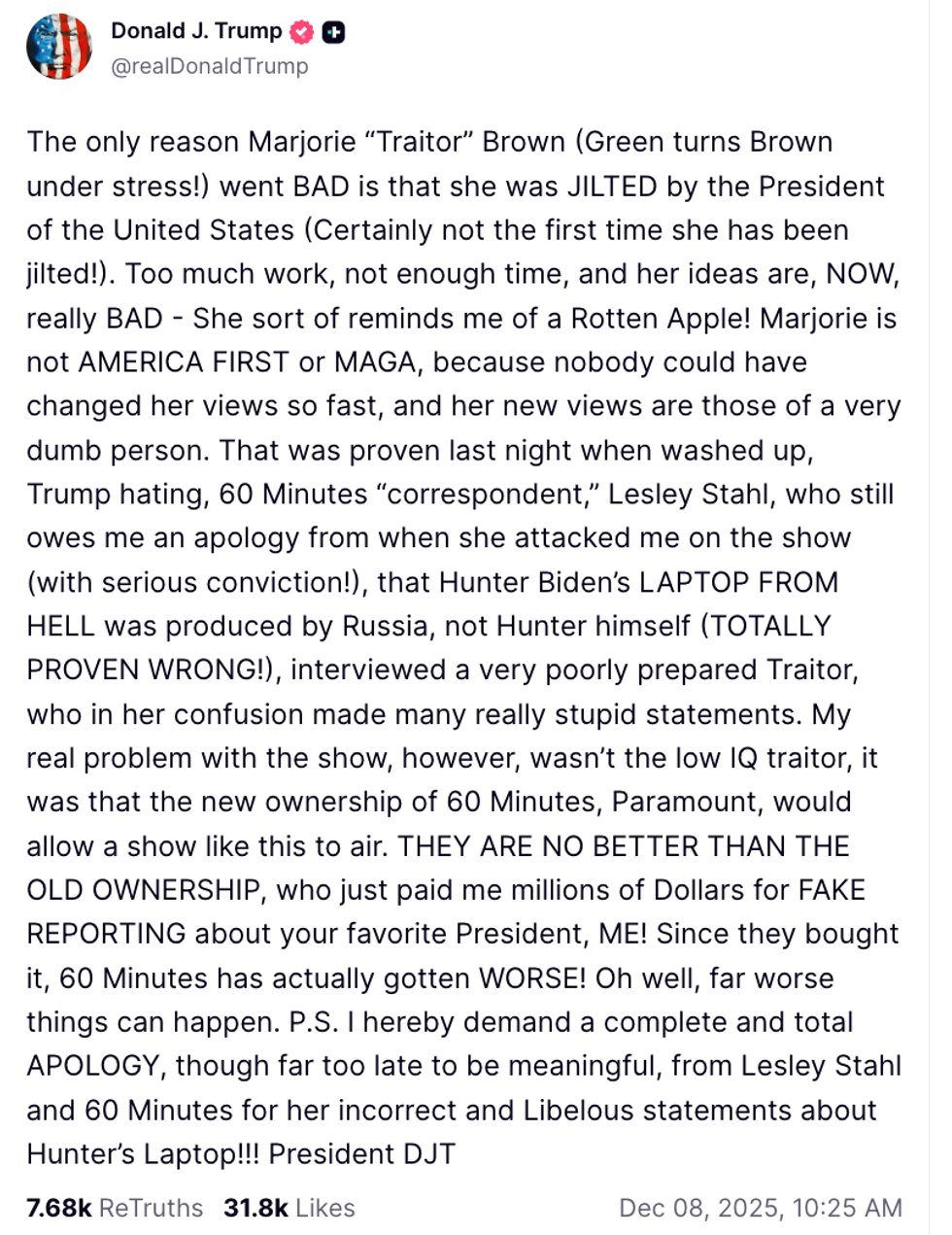

@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social

@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social