A survey of 150,000 students from across Virginia has led Francis Huang of the University of Missouri and Dewey Cornell of the University of Virginia that rates of bullying for 2017 have increased or decreased in certain areas depending on a political factor.

The researcher's findings, published in Educational Researcher, revealed higher rates of bullying in areas that voted for Donald Trump in the 2016 elections and lower rates of bullying in those that voted for Hillary Clinton.

According to the survey, seventh and eighth graders in areas that voted for President Trump were 18% more likely to witness or experience bullying, and 9% more likely to witness or experience bullying based on racial or ethnic background.

The scientists were quick to point out that these increased rates of bullying are not necessarily caused by Trump's election. Famously, correlation is not the same as causation, and it's possible both Trump's election and the higher rates of bullying are caused by a third, unknown factor, or that the two observations are only coincidentally related.

However, the inverse is also possible: that Trump's election played a role in children feeling like bullying is acceptable.

These results are a stark contrast from 2015, when researchers noted "no meaningful differences" in bullying rates from community to community, at least when comparing political affiliations.

Meanwhile, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have revealed that overall bullying rates nationwide have been consistent with past years, showing little change. According to the department's Youth Risk Behavior Survey, roughly 20% of students were bullied at school in 2017.

Dr. Huang believes these numbers match up with his study's nicely.

While areas that voted for Trump experienced an increase in bullying, those that voted for Hillary Clinton saw a decrease:

"If, in one area, bullying rates go up, and, in another area, your bullying rates go down, what do you get? You get an average of no change."

Dorothy Espelage, a psychology professor at the University of Florida, doesn't think the correlation is coincidental:

"Anybody that's in the schools is picking up on this. You don't have to be a psychologist or a sociologist to understand that if these conversations are happening on the TV and at the dinner table that these kids will take this perspective and they're going to play out in the schools."

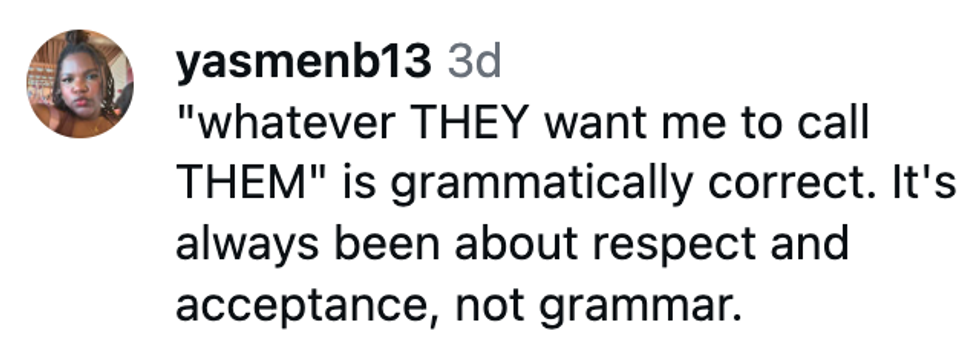

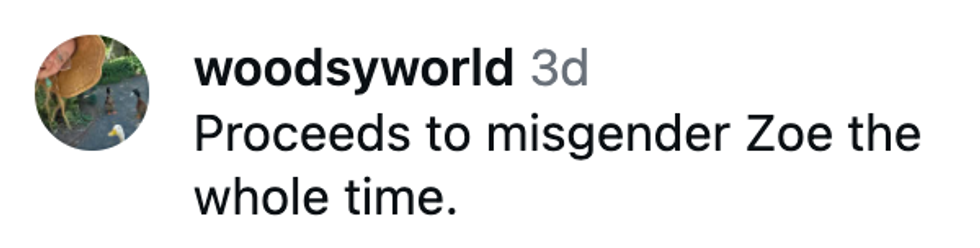

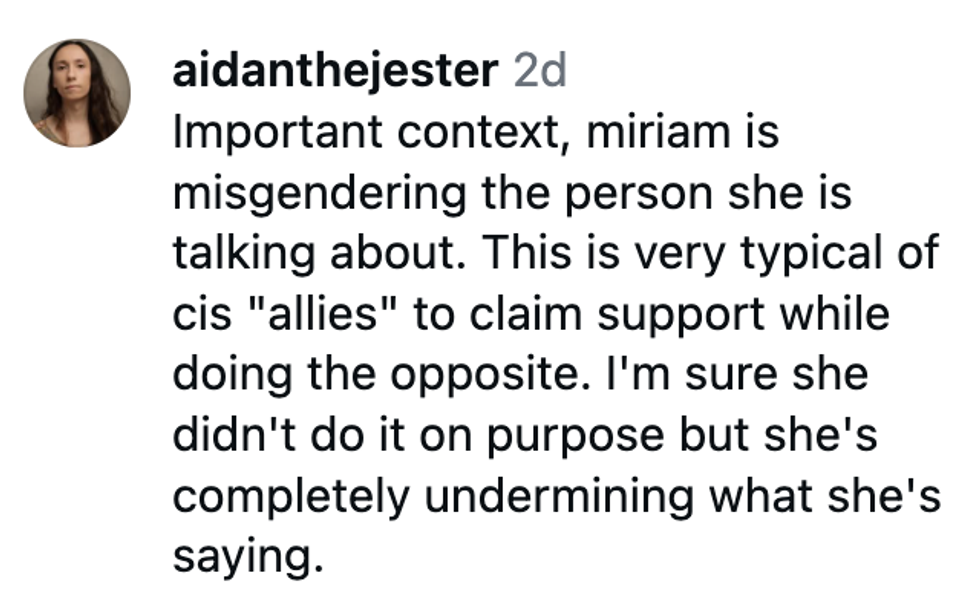

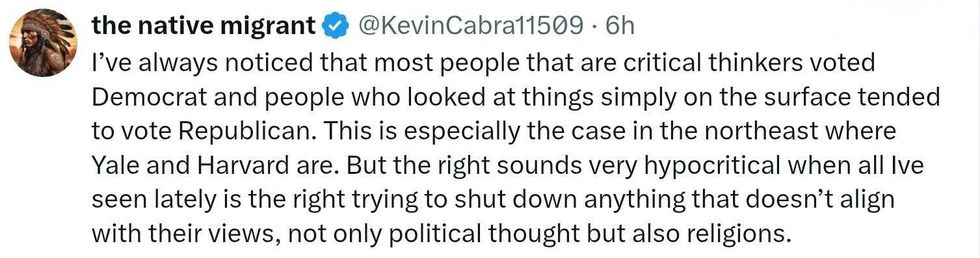

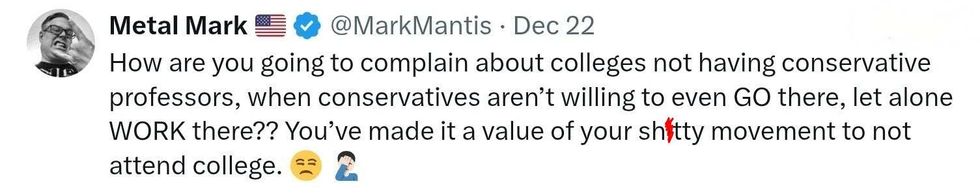

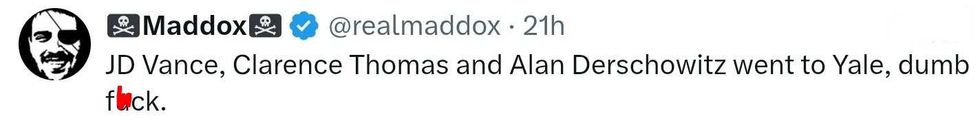

Twitter users were not at all surprised by the results of the survey:

A national survey conducted this past fall showed that only 14% of children aged 9-11 thought the country's leaders were good role models who treat others with kindness. Cornell noted in a statement:

" Parents should be mindful of how their reactions to the presidential election, or the reactions of others, could influence their children. And politicians should be mindful of the potential impact of their campaign rhetoric and behavior on their supporters and indirectly on youth."

Huang still hasn't lost hope for the future, however:

"...bullying is something that can still be addressed and brought down in schools."

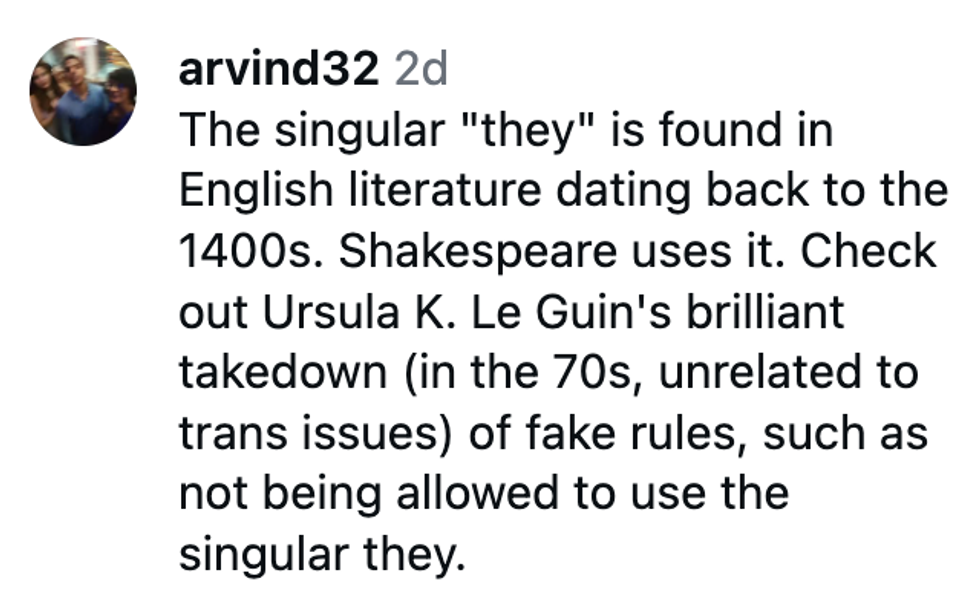

replying to @elonmusk/X

replying to @elonmusk/X replying to @elonmusk/X

replying to @elonmusk/X replying to @elonmusk/X

replying to @elonmusk/X replying to @elonmusk/X

replying to @elonmusk/X

Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook