Eighteen months of investigations. Over 1000 witness transcripts. A series of explosive and gripping public hearings throughout the summer and fall of 2022. A voluminous and exhaustive final report.

And now, at long last, a formal vote to refer criminal charges against former president Donald Trump to the Department of Justice, as well as possible other charges against his key cohorts, including John Eastman, Rudy Giuliani, and Mark Meadows.

The January 6 Committee understands that its work has all come to this point. Through a bipartisan and likely unanimous vote in its final public hearing on Monday, the Committee reportedly will recommend three criminal charges against former president Trump.

The charges will include the following:

- 18 U.S.C. 2383, insurrection

- 18 U.S.C. 1512(c), obstruction of an official proceeding

- 18 U.S.C. 371, conspiracy to defraud the United States government

But what does this criminal referral actually mean for the ongoing criminal investigation, now led by Special Counsel Jack Smith?

And how likely is it that the Department will proceed with each of them?

Let’s start by reviewing the impact of the expected criminal referrals by the Committee, then discuss in broad terms what each of the possible charges entails.

So Is This a Big Deal or Nah?

The Committee’s detractors, as well as those generally skeptical of the backbone of the Justice Department, are quick to point out that criminal referrals from a congressional committee do not carry any legal requirement by the Department to act. As such, they are advisory only and by definition without teeth.

Law enforcement receives referrals all the time from any number of sources, and in the end, they are all simply recommendations. At best, such referrals carry symbolic and political value, but even then they may wind up politicizing the investigation even further.

Yet this referral by the January 6 Committee stands apart. With it comes the release of over 1000 witness transcripts that the Justice Department is now free to review as part of its ongoing investigation.

And importantly, the criminal referrals will provide a clear prosecutorial roadmap for the Department should it wish to move forward with indictments. With respect to each recommended charge, the Committee will have set forth the legal basis for its recommendation as well as all relevant evidence that supports it, including witness testimony.

The roadmap will also help guide the Department in seeking further testimony and evidence, particularly where there are hearsay obstacles that might prevent existing testimony from being used in court. This is a gigantic time saver for the Department, akin to getting the full course outline with notes from a top notch student long before the final exam.

The Committee will also cite to relevant federal opinions where judges have already assessed the evidence and legal arguments and issued rulings in the Committee’s favor. These will include, for example, Judge David Carter’s ruling that Donald Trump and John Eastman likely committed the crimes of obstruction of an official proceeding and conspiracy to defraud the United States through their schemes around the election.

They will also include Judge Amit Mehta’s ruling that Trump’s language during the rally on January 6 plausibly incited violence.

These are the kinds of orders that will give the Department greater confidence that it can similarly succeed in its case and ultimately convince a jury to conclude beyond a reasonable doubt that Donald Trump is guilty.

The Insurrection Charge

While legal observers have long expected the Committee to recommend obstruction and fraud charges, given public statements by vice-chair Wyoming Republican Representative Liz Cheney that tracked the language of those statutes, the recommended insurrection charge comes as a bit of a surprise. It is a more controversial statute to charge, more difficult to prove, and more politically fraught for both the former president and the Department.

So what might be driving the Committee to include the charge in its criminal referral?

For starters, an insurrection charge would tie Trump directly to the violence at the Capitol, a key fact the Committee has been working hard to demonstrate to the American public.

The statute, 18 U.S.C. 2383, reads as follows:

“Whoever incites, sets on foot, assists, or engages in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States or the laws thereof, or gives aid or comfort thereto, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both; and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States.”

Pay attention to the words “incites,” “assists,” and “gives aid or comfort” in the language of the statute.

Trump may not have been present at the Capitol when the riot went down, despite a clear record that he really wanted, and did everything he could, to be there. But if Trump through his words incited the mob to attack, or if he assisted them or gave them any aid or comfort, he can be held accountable under the law.

There’s plenty of evidence that Trump is guilty of insurrection. To begin with, he called his followers to Washington to participate in a “wild” day.

Close advisors like Steve Bannon announced that “all hell” would “break loose” on January 6. Witnesses testified that Trump intended all along to send the mob to the Capitol in violation of the rally permit.

He worked the crowd into a frenzy knowing that they were armed because many couldn’t even get past his own metal detectors. His own advisers and rally organizers were scared about what he intended to do.

Once the violence began, Trump did not call for the National Guard, did not tell his followers to disperse, and even tweeted out an inflammatory message about then Vice President Mike Pence that caused the mob to surge forward in anger and call for Pence’s hanging—a sentiment of which Trump tacitly approved.

His staff tried repeatedly to get him to call off the attackers, but Trump resisted for over three hours. His intention was clear: If the rioters could stop Congress from finishing the electoral count, it could buy him time to go back to his allies in state legislatures and get them to decertify their states results.

Against this array of evidence, Trump will assert his First Amendment right to speak and to urge—metaphorically, he would argue—his followers to “fight.” He will protest that his words were too far removed from the site of the violence to connect him as their chief cause.

And he will point to moments in his speech and in his tweets where he urged protestors to go “peacefully” and to not attack the Capitol Police. Prosecutors would need to establish that his occasional nods to “peaceful” protest did not overcome the clear intent by Trump to unleash the mob and assist it through his intentional dereliction of duty and his inflammatory tweets.

A jury would need to decide unanimously that these defenses did not raise any reasonable doubts over Trump’s incitement, assistance or aiding and abetting of the insurrection.

With all this, it’s not by any means a slam dunk case, and the Justice Department will need to weigh whether it thinks it can win it, or whether it will proceed only with the non-violent charges of obstruction and fraud.

This is a weighty decision; as the final clause of the statute states, those found guilty under it are ineligible to hold office in the U.S. Thus, the decision whether to charge Trump with insurrection carries enormous potential political consequences for the nation.

One further note: There is a nerdy separation of powers question here over whether Congress, through legislation, has the power to alter the eligibility of candidates for the co-equal executive branch.

But that might not matter, because a conviction of insurrection would also presumably trigger Section 3 of Amendment XIV to the Constitution, which bars from federal office anyone who has “engaged in insurrection.”

The Obstruction of an Official Proceeding Charge

It was over a year ago that Liz Cheney signaled to the country that the Committee was exploring whether Donald Trump obstructed Congress in violation of 18 U.S.C. 1512(c).

That statute reads:

“Whoever corruptly, or by threats or force, or by any threatening letter or communication influences, obstructs, or impedes or endeavors to influence, obstruct, or impede the due and proper administration of the law under which any pending proceeding is being had before any department or agency of the United States, or the due and proper exercise of the power of inquiry under which any inquiry or investigation is being had by either House, or any committee of either House or any joint committee of the Congress—Shall be fined under this title, imprisoned not more than 5 years or, if the offense involves international or domestic terrorism (as defined in section 2331), imprisoned not more than 8 years, or both.”

It is notable that many prominent January 6 defendants who stormed the Capitol on that day were later charged with obstructing the electoral count by Congress.

In other words, the Department has test driven this argument before judges already and likely feels confident that it can make the case with others, including possibly Donald Trump.

As I wrote about this past June, the question of Trump’s culpability under this statute may rest upon a single word: “corruptly.”

While the Supreme Court has not weighed in directly on what this word means win the context of Section 1512(c), as legal commentator Joyce Vance has noted, in similar contexts, such as in neighboring Section 1505, it generally means “acting with an improper purpose, personally or by influencing another, including making a false or misleading statement, or withholding, concealing, altering, or destroying a document or other information."

There’s a mountain of evidence that Trump acted “corruptly” to halt the electoral count. Behind the scenes, he was conspiring with John Eastman to convince Mike Pence to overstep his authority and upend the count by unilaterally declaring the electoral votes of the swing states invalid.

Judge Carter called this plot a “coup in search of a legal theory.” Trump’s campaign oversaw the creation of fake elector slate certifications that were transmitted to Congress in the hopes that they would give Pence a justification to throw the election to Trump, or at least delay certification by Congress long enough for state legislators to decertify their state results.

And on the day of the count itself, as the riot raged, Trump acted corruptly by simply standing by and doing nothing, when he had it solely within his power to stop the attack.

Against this evidence, Trump will argue that he was within his legal rights to urge Pence to refuse to count the votes of states where, he asserts, there was doubt as to the validity of the election.

Whether his actions were permitted or not was something that a court could later decide, he would add, and so long as he had a colorable legal argument that Pence had such authority, then he did nothing wrong.

After all, there’s currently a big effort underway to clarify the vice president’s role in the electoral counting, so Trump would argue that he can’t be held liable for pressing his case via an ambiguity in the law.

Here, the Department should have greater confidence that these arguments are unsound. For starters, they were already tested before Judge Carter in the context of a civil challenge by John Eastman to the production of attorney-client communications.

The assertion of privilege by Eastman was overcome in a resounding victory by the Committee in March of 2022, where Judge Carter found that the “crime-fraud exception” to the privilege applied.

In essence, the court agreed with the Committee that communications between Eastman and others, including Trump, were not privileged and therefore had to be turned over because Eastman and Trump likely used thse communications in the commission of two federal crimes of obstruction and fraud.

Judge Carter also pointed out that if Trump wanted to claim that Vice President Pence had some kind of unilateral power to overturn the election, the place to do so was in court, and not through an unconstitutional power grab.

Because many of the facts behind the Eastman plot are uncontested, a federal judge will likely decide what defenses Trump and Eastman can and cannot raise at trial. Given the record to date, Trump and Eastman aren’t likely to get much mileage out of the argument that they were exercising some kind of lawful interpretation of the Electoral Count Act.

It is also uncontested that while the attack on the Capitol raged, Trump did nothing to stop it. To date, Trump has offered no explanation for his inaction, leaving only the obvious one that he actually wanted the attack to continue because it benefitted him.

That fits the definition of “corruptly” fairly nicely. On this point, the testimony before the grand jury from advisors such as White House counsel Pat Cipollone may prove pivotal. He and others will be able to shed light on Trump’s state of mind during the assault, and it will be up to Trump to rebut the clear evidence that he was acting with corrupt intent.

Given these considerations, it is more likely that the Department will bring charges under the obstruction statute than the insurrection statute. Trump’s defenses here are far less sound and so far largely absent, even in his public missives.

The Conspiracy to Defraud the United States Charge

When people make a plan and set out to defraud the government, that’s when 18 U.S.C. 371 kicks in.

That statute reads:

“If two or more persons conspire either to commit any offense against the United States, or to defraud the United States, or any agency thereof in any manner or for any purpose, and one or more of such persons do any act to effect the object of the conspiracy, each shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.”

There are multiple levels to the fraud that the Trump White House and Trump Campaign sought to perpetrate.

One clear one is the organizing of fake electors in critical swing states to give the false impression that there were contested election results from those states. That fraudulent scheme then would provide Mike Pence a legal hook for what they wanted him to do on January 6.

Another level is the coordinated spreading of the Big Lie by the Trump Campaign about a stolen election, which found its way into nationwide pressure campaigns on state legislators and five dozen or so failed lawsuits to overturn the election results. Trump and his campaign aides knew that they had lost the election fair and square, the Committee has shown, but they persisted in repeating false claims about election fraud in order to try to hang onto power.

Trump’s main defense here will be that he sincerely believed the fiction he was telling or was simply blind to the truth of it. But this may not avail him, and again, as I wrote about earlier this year, this didn’t work with Judge Carter.

After all, just because you may wrongly believe something is true doesn’t give you the right to undertake illegal actions to advance your cause. Your actions are still illegal even if your belief was mistaken.

Moreover, if you make yourself willfully blind to the truth, you can’t escape accountability.

For this reason, it is somewhat more likely that the Department of Justice will pursue an indictment for conspiracy to defraud than, say, an insurrection charge, because Trump’s defenses here not only are weak but have failed before a judge before.

So What Now?

No one can know the mind of the new Special Counsel on this, but it is safe to say that he is familiar with the excellent team of former federal prosecutors who have led the staff work of the January 6 Committee and likely will give considerable weight to their investigations and conclusions.

In the end, it would come as a surprise if at least two of the three charges that the Committee has recommended are ultimately not brought, and it is quite possible that all three will be.

But this won’t happen right away.

The handover of materials by the Committee to the Department will take time to review, and follow up work will be necessary, particularly where evidence in its current form is inadmissible due to the rules of evidence at trial, which are more stringent than those around Congressional testimony.

We will have to be patient as the process grinds forward yet again, but make no mistake: The criminal referrals comprise a critical milestone in this long saga, and we are now entering a new stage of the case entirely.

Columbia Heights Public Schools

Columbia Heights Public Schools

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Gym Weights GIF by Guava Juice

Gym Weights GIF by Guava Juice

Man With A Plan

Man With A Plan  Happy Feeling Good GIF by BEARISH

Happy Feeling Good GIF by BEARISH  Roadside Assistance Flat Tire GIF

Roadside Assistance Flat Tire GIF

u/Murky_Chemical891/Reddit

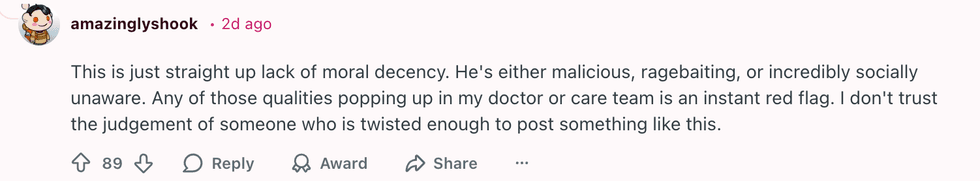

u/Murky_Chemical891/Reddit u/amazinglyshook/Reddit

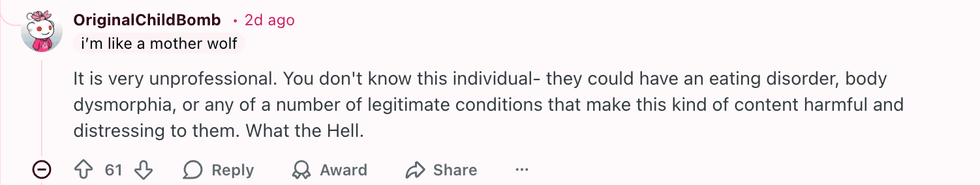

u/amazinglyshook/Reddit u/OriginalChildBomb/Reddit

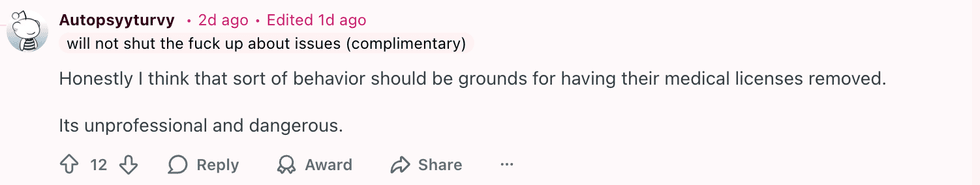

u/OriginalChildBomb/Reddit u/Autopsyyturvy/Reddit

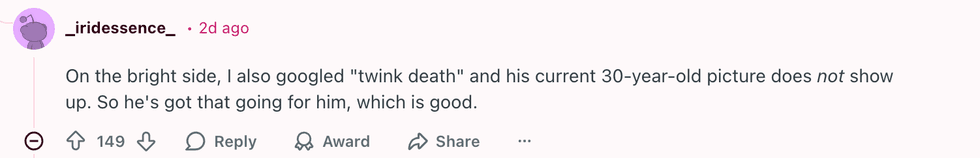

u/Autopsyyturvy/Reddit u/_iridessence_/Reddit

u/_iridessence_/Reddit u/HallWild5495/Reddit

u/HallWild5495/Reddit u/fandomnightmare/Reddit

u/fandomnightmare/Reddit  u/SpecificBeyond2282/Reddit

u/SpecificBeyond2282/Reddit u/DvorakThorax/Reddit

u/DvorakThorax/Reddit u/SeaRespond9836/Reddit

u/SeaRespond9836/Reddit u/According-Garden-129/Reddit

u/According-Garden-129/Reddit

@its.avelyn/TikTok

@its.avelyn/TikTok @its.avelyn/TikTok

@its.avelyn/TikTok @its.avelyn/TikTok

@its.avelyn/TikTok @its.avelyn/TikTok

@its.avelyn/TikTok @its.avelyn/TikTok

@its.avelyn/TikTok @its.avelyn/TikTok

@its.avelyn/TikTok @its.avelyn/TikTok

@its.avelyn/TikTok @its.avelyn/TikTok

@its.avelyn/TikTok @its.avelyn/TikTok

@its.avelyn/TikTok @its.avelyn/TikTok

@its.avelyn/TikTok