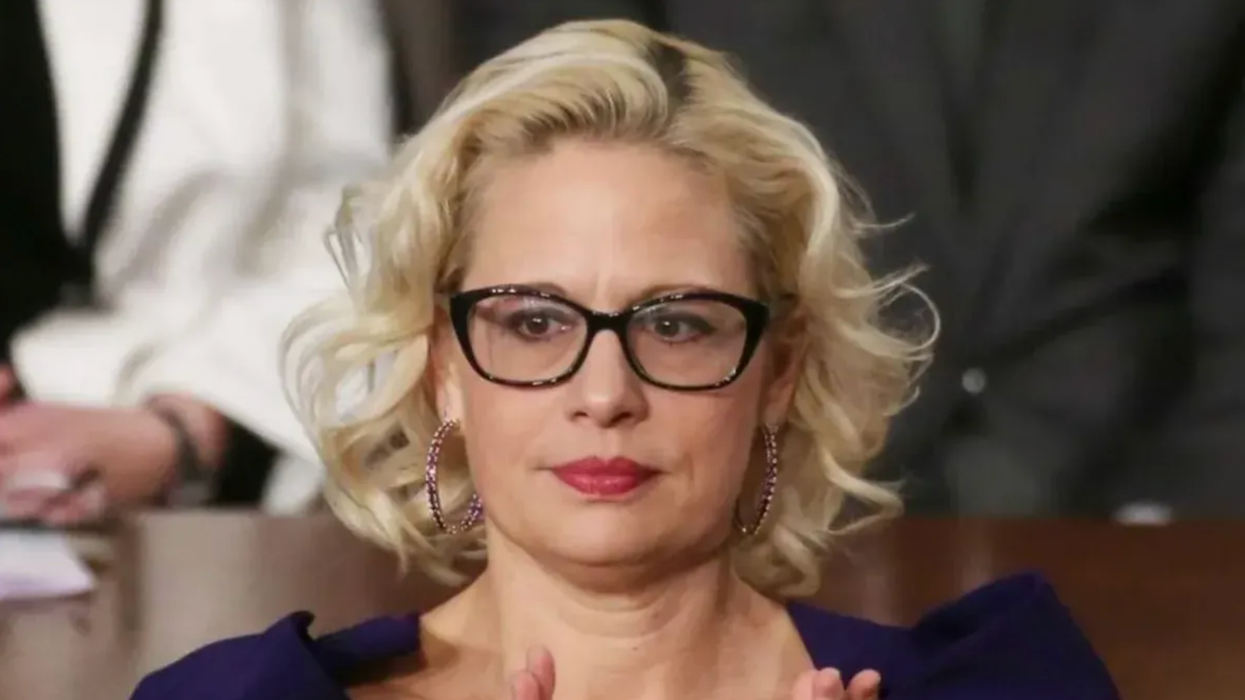

Hiding somewhere in Joe Manchin's shadow is erstwhile progressive turned enfant terrible of the Democratic Party, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, whose recent attempted seizure of the maverick mantle from the late Sen. John McCain is nothing short of embarrassing—especially for a senator who has served all of six months but who still loves to lecture about how the chamber is supposed to work. (Slate's description of Sinema as having "Toxic White Lady Energy" seems apt whenever she purports to tell minority voters, who have fought for decades for the right to vote, that she knows how best to govern and what's best for them.)

Sinema recently penned an OpEd strawman for the Washington Post that she no doubt hoped would garner enough attention and vitriol from the left that she could spin it into gold. But she raises one substantive point that needs to be addressed because it is so often repeated as gospel without due consideration or evidence. As a rationale for keeping the filibuster, Sinema conjures the bogeyman of "repeated radical reversals in federal policy, cementing uncertainty, deepening divisions and further eroding Americans' confidence in our government." After all, if a simple majority can change the law (what a concept!) then wouldn't this just ping-pong us forever between ever-shifting control of Congress? What about the rights of the party in the minority to move with more deliberation and for Americans to experience fewer political vicissitudes?

First, the Founders already addressed this question structurally. They did so by making one chamber of Congress (the House) representative by population and the other chamber (the Senate) representative by state, irrespective of population. This meant that the interests of rural, less populated states (e.g. Wyoming, the Dakotas, Nebraska, Idaho, Montana, all of which today are generally more conservative than the big states) already have a built-in advantage in the Senate.

We often forget that the current Senate already plays out on a tilted board, with smaller states having a far bigger say by design. The Founders actually were strongly against anti-majoritarian rules; the bicameral national legislature was their great compromise to give voice to the smaller states. They would have been appalled at the filibuster which gives those small states effective veto power.

Second, there isn't much evidence to support the idea that programs enacted by one party when they are in power get undone as a matter of course by the next. When big legislation passes, the people then have a chance to weigh in on it. If the program proves very popular, it's very hard to get rid of it, even if you have the majority.

This is precisely what happened with the Bush tax cuts and the ACA: Neither party succeeded in getting rid of them when they assumed power afterwards. McConnell couldn't even get 50 votes from his party to kill the ACA when he didn't need the filibuster to do so under budget reconciliation, which evades the filibuster rule.

Why can't the next party in power easily undo the legislative acts of the last Congress? In part, it's because the people speak out. When the GOP came for the ACA, town halls were filled by citizens demanding the government not take away their healthcare. The threat to healthcare was a driving force behind the GOP's midterm losses in 2018. And the centrists in the GOP (i.e. McCain, Murkowski, and Collins) weren't ready to ignore those voters.

Finally, what the filibuster does wind up encouraging, because it gridlocks Congress so effectively, is ever greater presidential power and governance through executive fiat. If anything feels ping-ponged lately, it is how one person in the Oval Office can change so much through the stroke of a pen, only to have it undone four years later. This is also something the Founders also would be appalled by because they mistrusted would-be kings and wanted Congress to be the branch of government that actually legislated. The less power Congress has to actually do the will of the people, the more the people will invest that expectation into the White House and its executive orders, with disastrous consequences should the wrong man for the country be elected.

In sum, the filibuster puts its finger on the scale of legislation far more than intended by the Founders (who had already accounted for the rights of smaller states), it isn't the reason that major laws aren't immediately undone by the next Congress, and it encourages those same wild swings to emerge via executive actions by the President. Senator Sinema may think she is saving Congress from itself by standing by the filibuster rule, but she's actually hobbling the legislative branch while disrespecting the clear intent of our Founders.

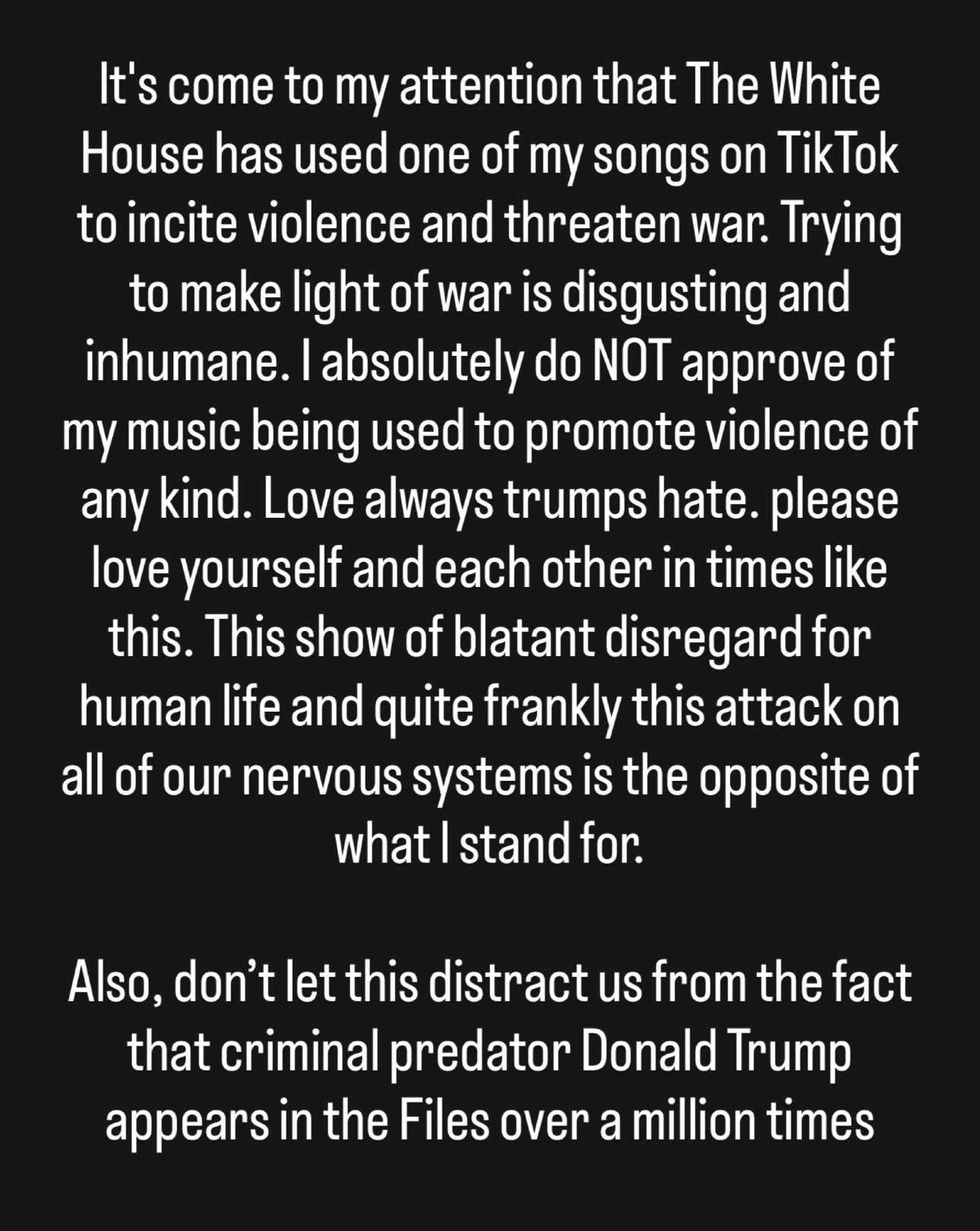

@KeshaRose/X

@KeshaRose/X