Please sit down before you read this article. What you're about to read will shock you.

Penises in Australia are shrinking.

To be fair, it may be happening globally, but the research and data are based in Australia.

Associate Professor Andrew Pask and Dr. Mark Green of Melbourne University have been researching male reproduction in Australia. Their findings took them aback.

Now the two researchers believe human being's exposure to chemicals present in plastics have, over generations, reduced penis sizes and increased the number of birth defects present in humans.

The chemicals they're most worried about are known as "endocrine disruptors," which can sometimes mimic sex hormones. In animals, the introduction of such chemicals can lead to symptoms like "infertility, undescended testes, and hypospadia."

However, it's important to point out that no studies have direct evidence of what the chemicals do to humans. The Melbourne studied found the data from animals as a plausible reason for their own findings of smaller penis sizes.

Perhaps the reason there are no such studies is because the chemicals are already naturally present in our blood, not unlike many of the other chemicals found in plastic. Pask and Green, however, believe our exposure to surplus levels of endocrine disruptors is causing additional problems.

Their biggest concern is hypospadia.

Hypospadia is a birth defect in the development of male genitalia where the urethra places its outlet for expelling urine anywhere on the penis from "shaft to scrotum," rather than the penis tip (where things work best). Hypospadia causes a plethora of issues, most notably intense difficulty urinating.

In 2007, a study was published claiming the rate of hypospadia had doubled in Australia from 1980 to 2000.

Now, according to that study, 1 in 118 babies carries the defect. Hypospadia is almost always surgically corrected during infancy.

When scientists around the world made attempts to corroborate the study's data, however, most of them "reported the data was too inconsistent to draw strong conclusions."

Pask, however, believes the data and believes the problem is growing worse:

No one likes to talk about this.

Often parents don't even like to tell their kids they had it – it gets surgically repaired but often the surgeries don't work very well...

When [Hypospadia] is doubling, it cannot be genetic defects – it takes years for that to spread through a population.

So we know it has to be environmental in origin.

The duo believe another endocrine disruptor may mimic the effects of the female sex hormone estrogen. An excess of estrogen in a developing male can shorten penis length. However, their data doesn't speak to this effect at a full-population level.

Dr. Green points out that the effects of these chemicals become more potent from generation to generation, with effects particularly noticeable by the third generation:

Humans have been exposed to these since the 1950s, so about two generations.

Professor Peter Sly, director of the World Health Organisation Collaborating Centre for Children's Health at the University of Queensland, also thinks there may be some validity to the duo's studies:

There is a lot of evidence out there.

There is human-level data.

Associate Professor Frederic Leusch, an environmental scientist at Griffith University, also made it clear that the effects Pask and Green are speaking of have been undeniably proven in animals.

But Leusch says studies should be done on humans before any huge statements are made:

We have clear, indubitable, mechanistic-linked evidence from animals this can happen.

Humans are animals. And we know these chemicals are in our bodies.

So it's absolutely possible. But we still cannot be sure.

The National Industrial Chemicals Notification and Assessment Scheme has issued a statement in response to Green and Pask's findings:

The Department monitors scientific literature and liaises with other regulators, nationally and internationally, to maintain an up-to-date understanding of the status of research on endocrine-active chemicals and will recommend risk management actions to mitigate a significant adverse health effect if there is sufficient evidence of adverse outcomes from exposure to an endocrine disruptor.

It seems scientists haven't yet settled on a conclusion and proper course of action regarding Australian penis length or Hypospadia, but one can only hope this potential disaster will be solved soon.

Awkward Pena GIF by Luis Ricardo

Awkward Pena GIF by Luis Ricardo  Community Facebook GIF by Social Media Tools

Community Facebook GIF by Social Media Tools  Angry Good News GIF

Angry Good News GIF

Angry Cry Baby GIF by Maryanne Chisholm - MCArtist

Angry Cry Baby GIF by Maryanne Chisholm - MCArtist

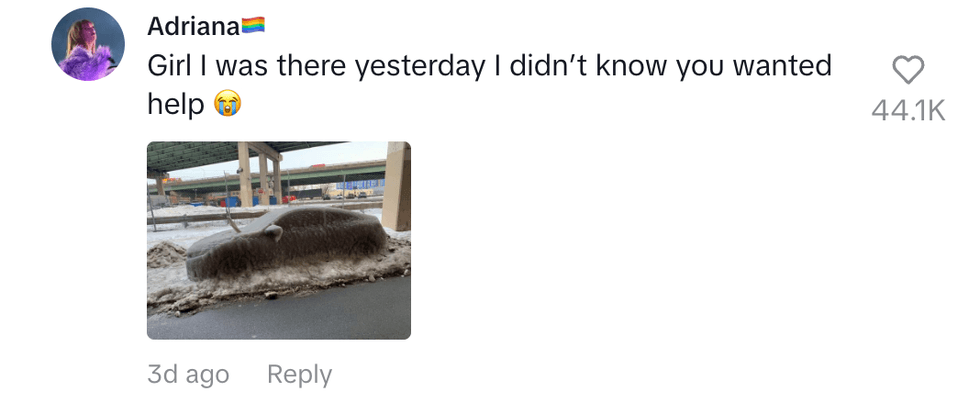

@adriana.kms/TikTok

@adriana.kms/TikTok @mossmouse/TikTok

@mossmouse/TikTok @im.key05/TikTok

@im.key05/TikTok @biontrtwff101/TikTok

@biontrtwff101/TikTok @likebrifr/TikTok

@likebrifr/TikTok @itsashrashel/TikTok

@itsashrashel/TikTok @ur_not_natalie/TikTok

@ur_not_natalie/TikTok @rbaileyrobertson/TikTok

@rbaileyrobertson/TikTok @xo.promisenat20/TikTok

@xo.promisenat20/TikTok @weelittlelandonorris/TikTok

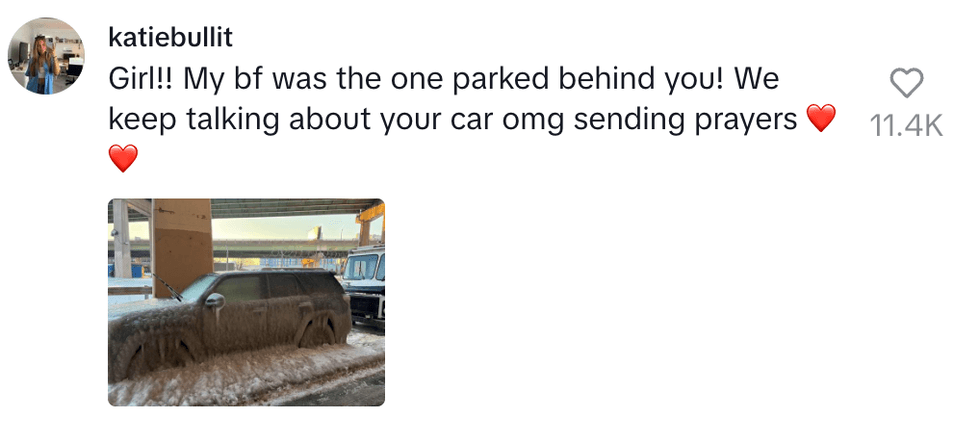

@weelittlelandonorris/TikTok @katiebullit/TikTok

@katiebullit/TikTok @rube59815/TikTok

@rube59815/TikTok

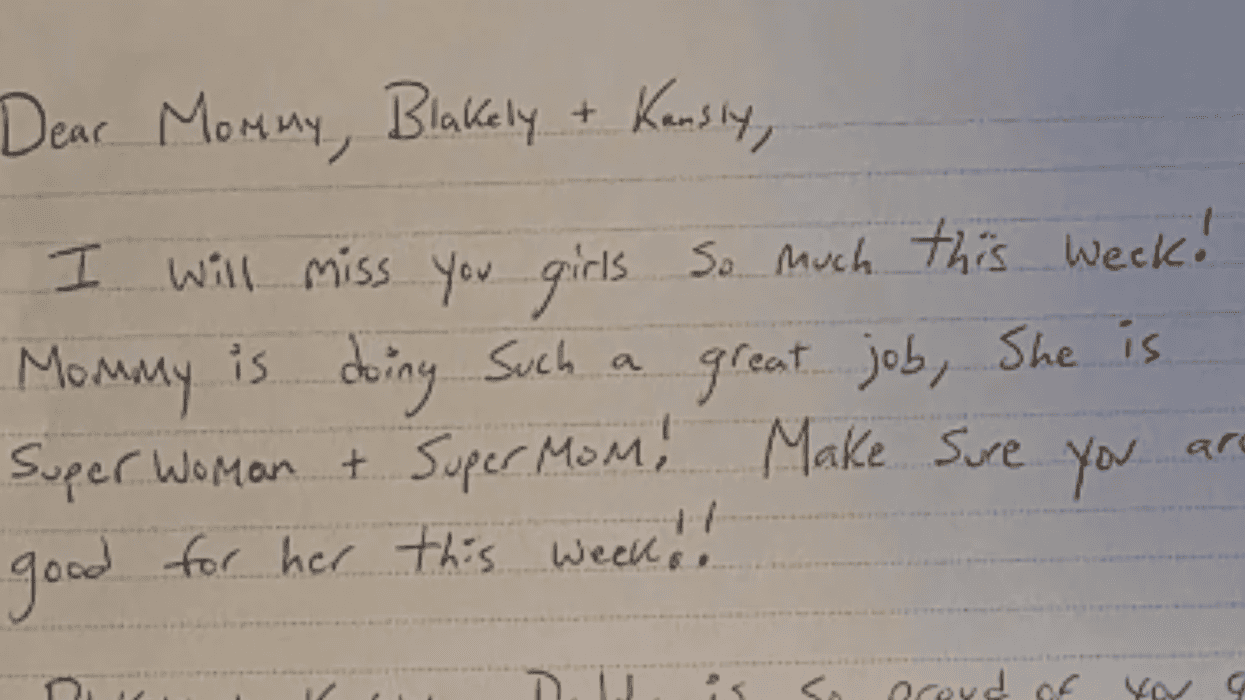

u/Fit_Bowl_7313/Reddit

u/Fit_Bowl_7313/Reddit

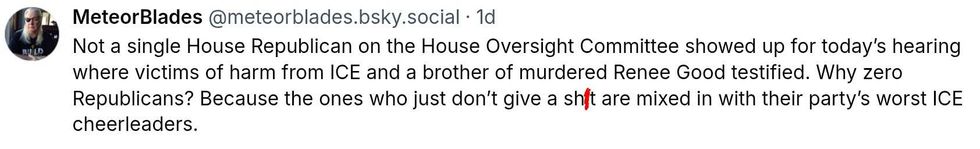

@meteorblades/Bluesky

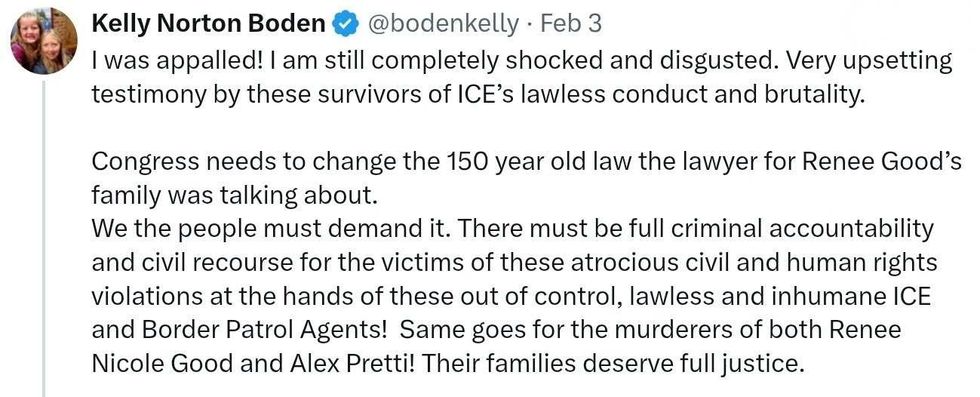

@meteorblades/Bluesky @bodenkelly/X

@bodenkelly/X