There’s a lot of talk in Washington around the so-called “debt ceiling” which is a really unfortunate name. I prefer to call it the “deadbeat ceiling.”

Why? A “debt” ceiling implies that what we’re talking about is like a credit card, as if Congress were voting whether or not to raise our borrowing limit.

As former Missouri Senator Claire McKaskill succinctly put it, however, this “is NOT raising your credit card limit, it is making your car payment.”

Let’s walk through why that is, and then I’ll explain why the correct framing of the issue may answer another important and pressing legal question: Can Joe Biden just ignore Congress and fix the deadbeat limit problem on his own?

Why the “debt limit” is a “deadbeat limit.”

With Republicans in charge of the House, the question is whether the GOP will turn the U.S. government into a deadbeat debtor. Deadbeats, if it even needs to be spelled out, are people who don’t pay the debts they promised to pay.

And that’s what this is really about.

You see, Congress already voted to pay for all the paychecks and programs that are supposedly now on the GOP chopping block. So by threatening to not pay them after the fact, they are trying to get two bites at this apple.

It would be as if you ran a big company and signed a lot of employee and vendor contracts, and then the next year you claimed:

“Well, I know I said I’d pay you, and I have that legal obligation, but I’m just not going to do that."

"Not unless you agree that I can either not pay you anything or pay you a lot less, now that you really need that money!”

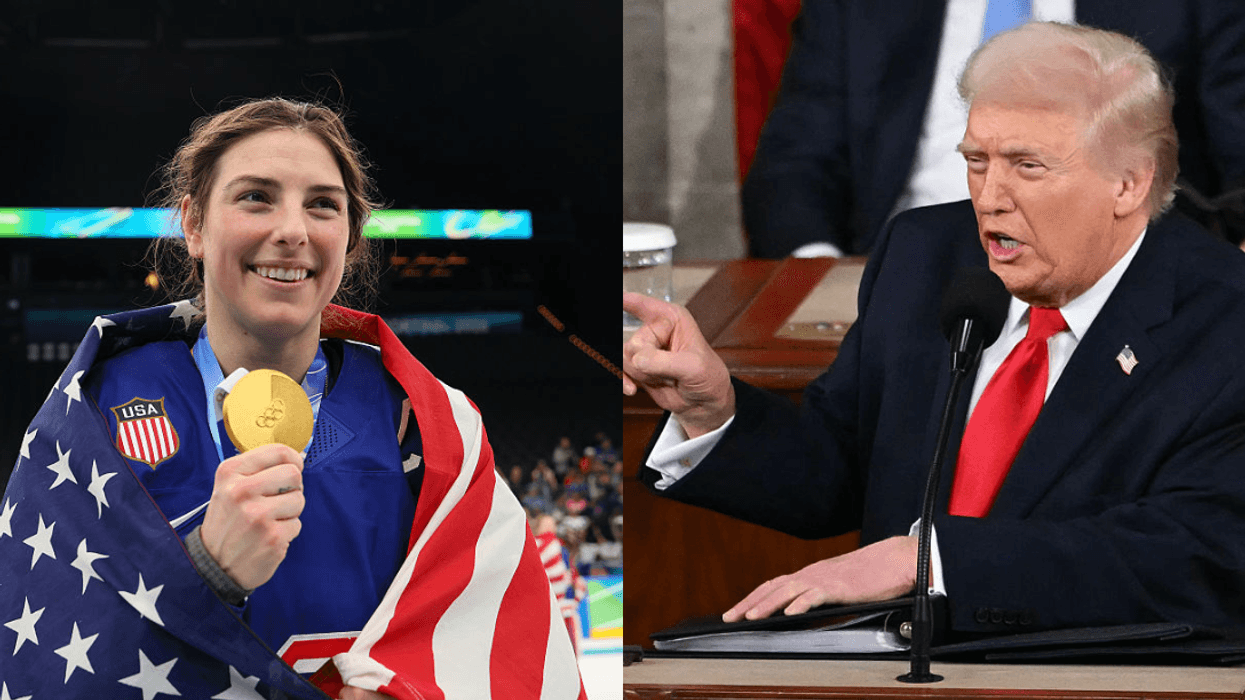

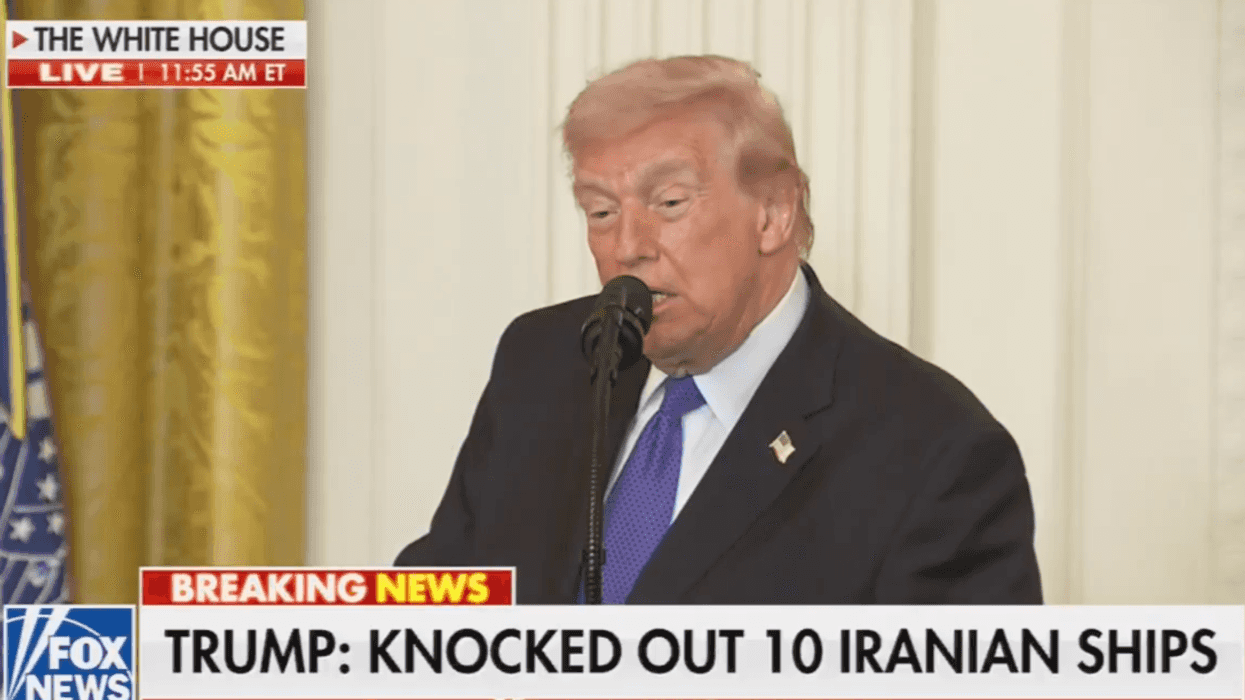

If this sounds familiar, this was the precise M.O. of the Trump Organization, which for years routinely stiffed small businesses, contractors and vendors out of the money they were owed and forced them to settle for pennies on the dollar rather than risk a protracted and expensive court fight.

By threatening to renege on payments it already agreed to, in this case by refusing to give the White House the authority to pay the nation’s debts, the GOP-led House is threatening to turn the U.S. government into a deadbeat debtor, just like the Trump Org.

And that’s why Joe Biden is right to refuse to even negotiate with them.

There’s nothing to negotiate, because the payment agreements were already made last year with the passage of the budget.

As Democratic Senator gBrian Schatz of Hawaii said plainly:

“In exchange for not crashing the United States economy, you get nothing.”

He continued:

“You don’t get a cookie…. You’re just a person doing the bare minimum of not intentionally screwing over your constituents for insane reasons.”

Responding to GOP calls Democrats join Republicans at the negotiating table, Schatz said:

“[T]here is no table.”

But could Biden go even further?

Could he not only refuse to negotiate, but actually take away the weapon that the GOP is holding to the head of the economy?

Let’s dive into one theory gaining steam.

Why do we keep ignoring the 14th Amendment?

We fought a civil war to achieve it. It has some of the strongest protections of our democracy built into it, including a whole Section 3 against insurrectionists serving in the government.

Its language is plain and unequivocal. So what’s with Congress, the White House and the courts constantly skipping over the 14th Amendment?

That’s the question some notable legal minds are pondering as they consider Section 4 of the Amendment, which relates directly to the question of the satisfaction of government debts.

That passage reads as follows:

"Section 4: The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned."

Some context here: Section 4 was added to settle any doubt over the validity of bonds issued during the Civil War, in case Confederate forces came back into power in Washington and wanted to mess with those.

The Supreme Court noted in Perry v. United States nearly 90 years ago that “its language indicates a broader connotation…. ‘[T]he validity of the public debt’… [embraces] whatever concerns the integrity of the public obligations,” and it applies to government bonds issued both before and after the adoption of the Amendment.

But what does it mean that the “validity of the public debt” of the U.S. “shall not be questioned?”

As Harvard Law Professor Lawrence Tribe noted in July of 2021, the last time this debt ceiling crisis raised its head, Section 4 of the 14th Amendment “prohibit[ed] any default on Treasury’s obligations.”

But what’s a President to do when the Congress is threatening to drive the economy off the cliff by causing a default, in this case through inaction on raising the deadbeat ceiling?

Putting deadbeat debtor policy and messaging together.

There has been a notable shift in thinking among legal scholars, including Tribe, and it is one to which the White House should and probably will start to pay attention.

Years ago, legal and policy advisors told President Obama he lacked the authority to unilaterally raise the limit because, put simply, the power of the purse belongs to Congress and not the President. Fair enough, said Obama.

But then, with the economy in a potential tailspin from the brinksmanship by Congress, he wound up having to negotiate a compromise on debts already incurred and programs already funded, and only after serious harm was inflicted upon the economy through a credit downgrade of U.S. debt.

Not a terrific outcome for anyone.

But everyone missed something back then. While the Constitution does give the power over money generally to the Congress, the 14th Amendment expressly exempts from this power a default on U.S. public debt.

Such a default would be unconstitutional.

As Tribe notes, this actually sets up a tension between two different parts of the Constitution: Congress has power over our nation’s money, but the 14th Amendment also expressly prohibits default, so if “Congress fails to raise the debt limit, Executive action to avoid default arguably violates Congress’s exclusive power of the purse but is the lesser of two constitutional evils.”

We can work with this “lesser of two evils” approach, even before this Supreme Court. As University of Florida Law Professor Neil H. Buchanan, one of the chief proponents of this legal take, notes in his analysis, this means in effect that the 14th Amendment “requires the President to borrow to prevent a default”—one that would certainly “bring the validity of the public debt into question.”

This is a common sense reading of the Amendment.

It basically says while Congress has the power of the purse, it lacks the power to mess with the validity of public debts—and it shouldn’t be permitted to achieve that power through sneaky, sideways means never intended by the Framers. This is actually the only reasonable interpretation of this conflict, in my view.

But we can go even further.

It’s arguably the case that there’s no “tension” here at all in the Constitution. After all, what would Biden actually be doing by instructing the Treasury to raise the limit?

He would be affirming the Congressional power of the purse, not defying it. The thinking goes like this: When Congress passed the budget last year, that gave President Biden the precise instructions he needed to faithfully execute the law, including how much to spend and on whom.

There is no “other” law in tension here at all. They didn’t pass another budget. There’s just an unlawful threat by the GOP to violate Section 4 of the 14th Amendment.

That’s why it’s so helpful to think of this as a deadbeat instead of a debt limit. You avoid being a deadbeat by paying the bills you agreed to pay.

And you avoid enabling deadbeats by refusing to negotiate new terms with them after the fact, especially when the people who need the money—such as seniors, federal workers, families with children in poverty, and our veterans—are being taken as economic hostages.

If I were in the White House press office, my messaging advice would be this: Tell the American people you intend to faithfully execute the budget law passed last year by Congress, including who to pay and how much.

And if that includes raising the limit on borrowing in order to do so, you will do just that—because you refuse to turn the country into a deadbeat debtor like the Trump Organization.

@sko2535/Threads

@sko2535/Threads @hayderz/Threads

@hayderz/Threads @zetaplant2/Threads

@zetaplant2/Threads @dark_elle_akalisa/Threads

@dark_elle_akalisa/Threads @freeasfox/Threads

@freeasfox/Threads @mygirlfriday007/Threads

@mygirlfriday007/Threads drbenwayoperates/Threads

drbenwayoperates/Threads