On October 6, the Canadian government announced a provisional agreement with survivors of a Crown-Indigenous Affairs child welfare policy that resulted in an unknown number of illegal removals and adoptions of First Nations children.

Nicknamed “the Sixties Scoop,” the policy replaced the mandatory residential boarding school system as a means of forcibly assimilating Indigenous Canadians. Residential boarding school survivors previously settled a class action lawsuit in 2007.

Fighting back tears, Crown-Indigenous Affairs Minister Carolyn Bennett made the announcement. The settlement worth some Can$800 million (US$600 million) puts an end to years of contentious legal action under the direction of former Prime Minister Stephen Harper.

Minister Bennett said the move will "begin to right the wrong of this dark and painful chapter" caused by forcibly removing Indigenous children from their birth families. The children struggled in white foster homes and white adoptive families, sometimes in other countries.

They have lived their lives not being able to be proud Indigenous people. They have lived their lives not having secure personal cultural identity. That was robbed away. Someone thought that a non-Indigenous family somewhere else in the world was going to do a better job."

In February, Ontario Superior Court Justice Edward Belobaba found Canada had breached its "duty of care". Canada failed to take reasonable steps to prevent thousands of on-reserve children from losing their indigenous heritage during the '60s Scoop.

They suffered due to placement in non-aboriginal homes from 1965 to 1984 under terms of a federal-provincial agreement. Under Canadian law they lost their Native status once adopted and became, on paper, white.

The decision in the long-running and bitterly fought class action lawsuit paved the way for an assessment of damages. The lawsuit launched eight years ago sought $1.3 billion on behalf of about 16,000 indigenous children in Ontario.

Adopted by a non-aboriginal couple in 1972 at age nine, the lead plaintiff in the Ontario action, Chief Marcia Brown Martel, is a member of the Temagami First Nation near Kirkland Lake, Ontario. She later discovered the Canadian government had declared her original identity dead.

I feel like a great weight has been lifted from my heart. Our voices were finally heard and listened to. Our pain was acknowledged."

Newly appointed Indigenous Affairs Minister Carolyn Bennett said the Trudeau government would "absolutely not" appeal the ruling. She also suggested more than money was at stake.

It is really important that, as we begin these conversations about what is the best way forward for these survivors, we understand that what they are talking about are language and culture and the kinds of things that were taken from them, and they're things that a court can't really award. So, it's really important that we get to the table as quickly as possible."

Friday’s announcement is the culmination of those talks. While the original lawsuit covered only Ontario Natives, negotiations expanded the agreement to cover all of Canada. All First Nations and Inuit children removed from their homes between 1951 and 1991 can apply for compensation.

Talks continue for a final agreement, but the government set aside $750 million for individual compensation with $75 million for claimant legal fees. They earmarked another $50 million for a foundation dedicated to reconciliation initiatives

If more than 20,000 claimants, each individual will receive a payout of $25,000. If fewer than 20,000 claimants, each will receive up to a maximum of $50,000.

Indigenous survivors from as far away as Scotland and northern California rallied to hear the landmark announcement.

Most of the children adopted or placed in foster care weren’t educated about their Indigenous roots. By losing contact with their families and communities, they lost their language, culture and identity.

While not in all adoptive families, many children endured emotional, physical and sexual abuse and suffered lasting trauma. Some took their own lives. But implementation of this revised policy was due to the widespread abuse pervasive in the boarding school system.

“The court case that spurned this settlement found that there was a terrible legacy of emotional, mental and social problems affecting these people…,” stated Ian Austen who covered the story for The New York Times.

[A]s kids, they were bullied by white kids at school. So, they never felt, even if they were with a loving family, ...part of white... culture, but they really couldn’t go back home because they didn’t know the language... they had been completely pulled from that culture as well.”

So, there was this whole generation of people who grew up in kind of social, cultural, emotional limbo.”

Some children went into homes in Canada far from their ancestral lands. However others went to the US, UK, Australia and other countries.

Targeted white communities saw advertisements for the children.

Reactions to the settlement remain mixed. Among First Nations, in addition to celebration, the compensation package inspired anger and confusion.

“Government is getting off on the cheap,” said Ernie Crey, a chief of the Sto:lo Nation in British Columbia. Crey’s entire family grew up in white homes.

“It should have been in the billions. My stomach is churning and I am left feeling angry that government and the lawyers would basically conspire to sneak this deal through.”

I’ve lost younger siblings to the ‘60s Scoop. They are dead as a consequence.”

Anger is also the predominant reaction amongst non-Indigenous Canadians. Many only hear reparations, but don't know about the court order. Nor do they understand the history.

However, that's not a reflection of the opinion of all non-Indigenous Canadians. Those aware of the history feel the reparations justified.

“It's important to understand that the effects of Canada's residential schools didn't end when they closed, and didn't happen a long time ago." according to journalist Kevin Ma of the Saint Albert Gazette. "[It's] meaner, crueler sequel, the Sixties Scoop, kept going well through the 1980s, and, judging from the overrepresentation of Indigenous kids in child apprehension cases, still continues today."

This was racism, plain and simple, and it happened with our government's blessing. The fact that authorities thought it appropriate to rip babies from their mothers immediately after they were born would be absurd if it weren't so horrendous. I urge all of you to read up on this chapter of Canada's history, and encourage teachers to talk about it alongside lessons on the residential schools.”

Education is a good idea, as this is only the first step. In a statement to APTN News Saskatchewan lawyer Tony Merchant said scheduled negotiations continue into 2018.

“(We will also seek) additional compensation for loss of culture, and compensation for Metis and non-status Indians for whom Canada has no responsibility.” According to Merchant, Four law firms and Justice Michel Shore of the Federal Court negotiated the current package.

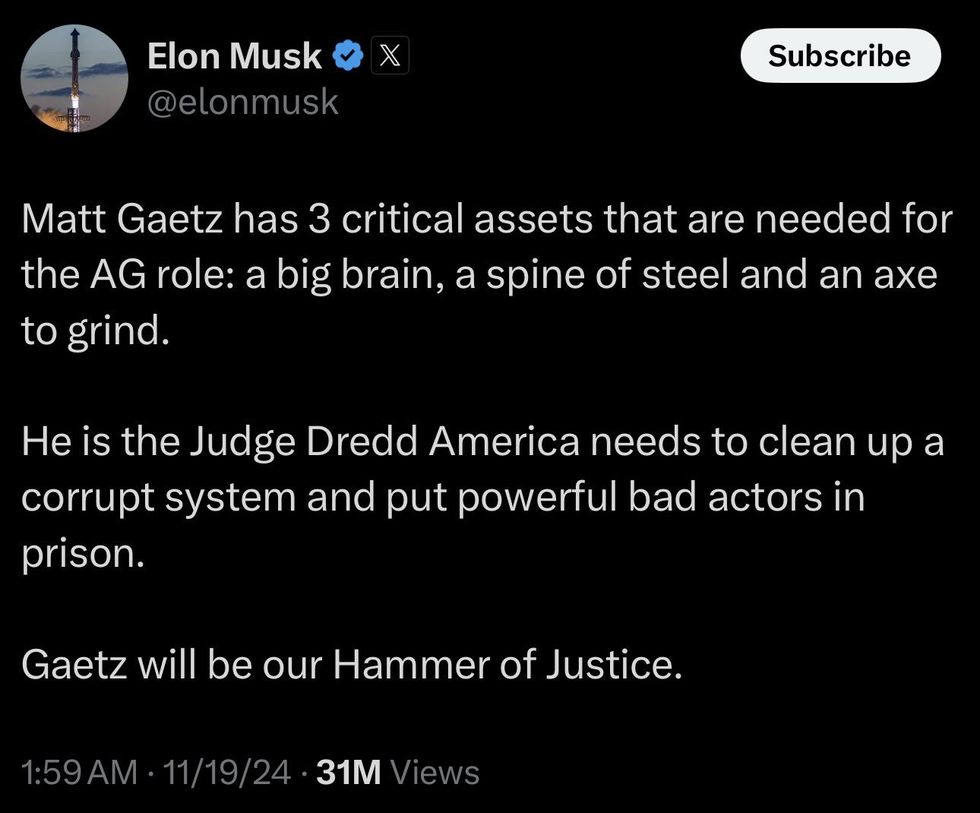

@elonmusk/X

@elonmusk/X

@thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram

@thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram @thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram

@thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram @thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram

@thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram @thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram

@thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram @thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram

@thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram @thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram

@thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram @thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram

@thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram @thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram

@thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram @thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram

@thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram @thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram

@thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram @thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram

@thedrewbarrymoreshow/Instagram

@shemdpodcast/Instagram

@shemdpodcast/Instagram @shemdpodcast/Instagram

@shemdpodcast/Instagram @shemdpodcast/Instagram

@shemdpodcast/Instagram @shemdpodcast/Instagram

@shemdpodcast/Instagram @shemdpodcast/Instagram

@shemdpodcast/Instagram @shemdpodcast/Instagram

@shemdpodcast/Instagram @shemdpodcast/Instagram

@shemdpodcast/Instagram @shemdpodcast/Instagram

@shemdpodcast/Instagram @shemdpodcast/Instagram

@shemdpodcast/Instagram